Abstract

Household storage of pharmaceutical is world-widely practice, including in Indonesia. The purpose of this study was to obtain the pattern of medicine storage, the sources and reasons of medicine kept in households. Acrosssectional survey was conducted on October 2011, involving 250 adult household respondents, randomly selected from three subdistricts in North Jakarta, and have approved the written consents, and interviewed with structured questionnaire. Data were performed in univariate and bivariate analysis with chi square test. The majority of household (82%) stored drugs at home; analgesic-antipyretic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory was the type of drugs kept by mostly (76.1%) of household. Out of 1001 stored drugs formulation encountered, about 31% were ethical drugs, mostly (64.8%) obtained from authorized pharmacies, purchased without prescription (71.9%), kept for future use (37.6%), and were leftover medicines (31.6%). Among the leftovers, 39.2% were ethical drugs including anti infective agents (31.5%). The leftover ethical medicines and anti infective agents could be indicated as inappropriate storage of pharmaceuticals and may lead to drug related problems. Penyimpanan obat di rumah tangga banyak dilakukan oleh masyarakat, namun tidak banyak informasi bagaimana obat disimpan dan digunakan oleh rumah tangga di Indonesia. Penelitian ini bertujuan memperoleh data pola obat di rumah tangga, sumber mendapatkannya, dan alasan obat disimpan. Survei potong-lintang dilakukan pada Oktober 2011, melibatkan secara acak 250 responden rumah tangga dewasa dari tiga kecamatan di Jakarta Utara yang dipilih purposif dan bersedia diwawancarai dengan menandatangani informed consent. Kuesioner terstruktur digunakan untuk memperoleh data obat. Dilakukan analisis data univariat dan bivariat dengan uji kai kuadrat. Mayoritas responden (82%) menyimpan obat, dengan jenis obat terbanyak analgesik-antipiretik dan anti-inflamasi nonsteroid (76,1%). Dari 1001 produk obat yang disimpan, 31% adalah obat etikal. Sebagian besar obat tersebut (64,8%) diperoleh dari apotek, dibeli tanpa resep dokter (71,9%), dan sengaja disimpan untuk persediaan jika sakit (37,6%) serta merupakan obat sisa resep (31,6%). Diantara obat sisa resep, sejumlah 39,2% adalah obat etikal, diantaranya termasuk anti-infeksi (31,5%). Adanya penyimpanan obat sisa resep berupa obat etikal dan anti-infeksi menggambarkan penyimpanan obat yang irasional dan dapat memicu masalah terkait obat termasuk risiko terjadinya medication error.

References

1. Hewson C, Shen CC, Strachan C, Norris P. Personal medicines storage in New Zealand. Journal of Primary Health Care. 2013; 5 (2): 146-50.

2. Nsimba SED, Jande MB. Household storage of pharmaceuticals, sources and dispensing practices in drug stores and ordinary retail shops in rural areas of Kibaha District, Tanzania. East and Central African Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2006; 9: 74-80.

3. Jassim AM. In-home drug storage and self-medication with antimicrobial drugs in Basrah, Iraq. Oman Medical Journal. 2010; 25: 79-87.

4. Directorate of rational use of medicines, MoH, Sultanate of Oman. Household survey on medicine use in Oman. 2009 [cited 2014 Feb 7]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents /s17055e/s17055e.pdf.

5. Tsiligianni IG, Delgatty C, Alegakis A, Lionis C. A household survey on the extent of home medication storage. A cross-sectional study from rural Crete, Greece. European Journal of General Practice. 2012; 18 (1): 3-8.

6. Patel MM, Singh U, Sapre C, Salvi K, Shah A, Vasoya B. Self medication practices among college students: a cross sectional study in Gujarat. National Journal of Medical Research. 2013; 3 (3): 257-60.

7. The benefits and risks of self medication. WHO Drug Information [serial on internet]. 2000 [cited 2014 Jan 11]; 14: [about 2 p]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jh1462e/1.html.

8. Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Surat Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan RI, Nomor: 949/MENKES/Per/VI/2000 tentang Registrasi Obat Jadi. Jakarta: Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia; 2000.

9. Grigoryan L, Ruskamp FMH, Burgerhof JGM, Mechtler R, Deschepper R, Andrasevic AT, et al. Self-medication with antimicrobial drugs in Europe. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2006; 12 (3): 452-9.

10. Yousif MA. In-home drug storage and utilization habits: a Sudanese study. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2002; 8 (2-3): 422-31.

11. Temu MJ, Risha PG, Mlavwasi YG, Makwaya C, Leshabari MT. Availability and usage of drugs at households level in Tanzania: case study in Kinondoni District, Dar es Salaam. The East and Central African Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2002; 5 (3): 49-54.

12. Ali SE, Mohamed IM, Ibrahim MIM, Subish Palaian S. Medication storage and self-medication behaviour amongst female students in Malaysia. Pharmacy Practice. 2010; 8 (4): 226-32.

13. Hussain S, Malik F, Hameed A, Ahmad S, Riaz H. Exploring healthseeking behavior, medicine use and self medication in urban and rural Pakistan. Southern Medical Review. 2010; 3 (2): 32-4.

14. De Bolle L, Mehuys E, Adriaens E, Remon JP, Van Bortel L, Christiaens T. Home medication cabinets and self-medication: a source of potential health threats? Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2008 Apr; 42 (4): 572-9.

15. Hughes CM, McElnay JC, Fleming GF. Benefits and risks of self-medication. Drug Safety. 2001; 24: 1027-37.

16. Direktur Jendral Pengawasan Obat dan Makanan Departemen Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Surat Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan RI, Nomor: 02396/A/SK/ lll/86 tentang Tanda Khusus Obat Keras Daftar G. Jakarta: Pengawasan Obat dan Makanan Departemen Kesehatan Republik Indonesia; 1986.

17. Direktur Jendral Pengawasan Obat dan Makanan Departemen Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Surat Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia No: 2380/A/Sl/Vl/83 tentang Tanda Khusus untuk Obat Bebas dan Obat Bebas Terbatas. Jakarta: Badan Pengawasan Obat dan Makanan Departemen Kesehatan Republik Indonesia; 1983.

18. Menteri Kesehatan RI. Surat Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor: 1331/MENKES/SK/X/2002 tentang Perubahan atas Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan RI No. 167/KAB/B.VIII/1972 Tentang Pedagang Eceran Obat. Jakarta: Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia; 2002.

19. Kelana A, Siregar E, Kumalasari F. Hati-hati obat palsu di sekitar kita. Majalah Gatra. 2013 [diakses tanggal 1 Februari 2014]; 4. Diunduh dalam: http://www.gatra.com/fokus-berita/27640-hati-hati-obat-palsudi-sekitar-kita.html.

20. Sabaté E, ed. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action [internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003 [cited: 2014 February 9]. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/ 9241545992.pdf.

21. Jin J, Sklar GE, Sen Oh VM, Li SC. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: a review from the patient’s perspective. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 2008; 4 (1): 269-86.

22. Goldsworthy RC, Schwartz NC, Mayhorn CB. Beyond abuse and exposure: framing the impact of prescription-medication sharing. American Journal of Public Health. 2008; 98 (6): 1115 – 21.

23. Ellis J, Mulan J. Prescription medication borrowing and sharing: risk factor and management. Australian Family Physician. 2009; 38 (10): 816-9.

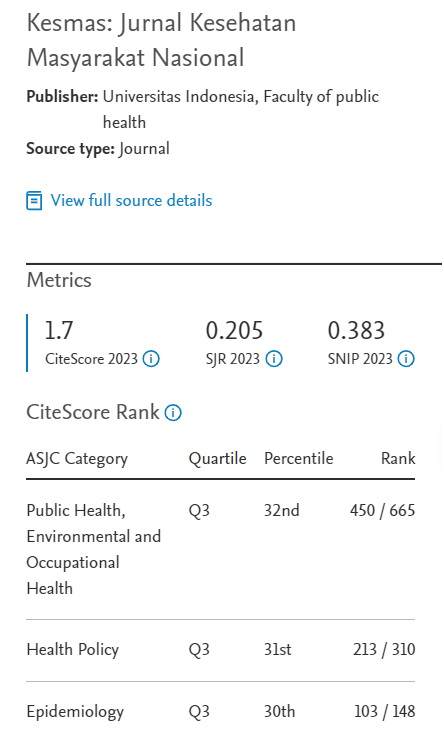

Recommended Citation

Gitawati R .

Pattern of Household Drug Storage.

Kesmas.

2014;

9(1):

27-31

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v9i1.452

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol9/iss1/5

Included in

Biostatistics Commons, Environmental Public Health Commons, Epidemiology Commons, Health Policy Commons, Health Services Research Commons, Nutrition Commons, Occupational Health and Industrial Hygiene Commons, Public Health Education and Promotion Commons, Women's Health Commons