Abstract

Pajanan pencemar udara selama kehamilan berhubungan dengan bayi berat badan lahir rendah (BBLR). Untuk menghubungkan konsentrasi NO2 dalam udara ambien, telah dilakukan studi ekologi di Jakarta. Konsentrasi NO2 didapat dari data monitoring BPLHD DKI Jakarta 2009 – 2011, sedangkan kasus-kasus bayi BBLR diperoleh dari Dinas Kesehatan Provinsi DKI Jakarta. Data dianalisis dengan Anova, uji korelasi, dan regresi linier dan berganda. Hasil analisis menunjukkan bahwa konsentrasi NO2 dalam bulan pertama dan kedua kehamilan berhubungan bermakna dengan BBLR (masing-masing dengan R = 0,464, nilai p = 0,0001 dan R = 0,243, nilai p = 0,013). Regresi linier berganda menunjukkan bahwa konsentrasi NO2 dapat meramalkan 25% kasus BBLR (R = 0,5; R2 = 0,25; nilai p = 0,0001). Variabel yang paling memengaruhi BBLR adalah pajanan terhadap NO2 pada bulan pertama gestasi (B = 259). Disimpulkan, pajanan NO2 pada bulan pertama dan kedua kehamilan dan tempat wilayah tinggal berhubungan dengan BBLR, dengan pajanan NO2 pada bulan pertama kehamilan merupakan faktor utama BBLR. It has been known that exposure to air pollutant during pregnancy was associated with low birth weight. To correlate NO2 concentration in ambient air with baby with low birth weight (LBW), an ecological study has been carried in Jakarta. NO2 concentration was obtained from 2009 – 2011 monitoring data (Jakarta BPLHD), while low birth weight data were obtained from Jakarta Provincial Health Office. Anova, correlation, linear and multiple linear regressions were employed to analyze NO2 concentration with LBW. It showed that NO2 concentrations during first and second month of pregnancy were significantly correlated with the LBW (R = 0.464, p value = 0.0001 and R = 0.243, p value = 0.013). Multiple linear regression showed that the concentration of NO2 in the first and second month of pregnancy can predict 25% of LBW cases (R = 0.5, R2 = 0.25; p value = 0.0001). The most influence variable on LBW is exposure to NO2 in the first month of gestation (B = 259). It is concluded that exposure to NO2 in the first and second month of pregnancy and city of residence correlated with the LBW, with NO2 exposure in the first month of pregnancy was the most influencing factor of the LBW.

References

1. Kwon HJ, Cho SH, Nyberg F, Pershagen G. Effects of ambient air pollution on daily mortality in a cohort of patients with congestive heart failure. Epidemiology. 2001; 12 (4): 413-9. 2. UNICEF. Child-info: monitoring the situation of children and women. New York: Division of Policy and Practice UNICEF; 2012. 3. Reagan PB, Salsberry PJ. Race and ethnic differences in determinants of preterm birth in the USA: broadening the social context. Social Science and Medicine. 2005; 60 (10): 2217-8. 4. Bibby E, Stewart A. The epidemiology of preterm birth. Neuro Endocrinology Letters. 2004; 25 (Suppl 1): 43-7. 5. Barker DJ. The origins of the developmental origins theory. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2007; 261(5): 412-7. 6. Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Riset Kesehatan Dasar 2007. Jakarta: Badan Penelitian dan Pengembangan Kesehatan, Kementerian Kesehatan RI; 2007. 7. Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Riset Kesehatan Dasar 2010. Jakarta: Badan Penelitian dan Pengembangan Kesehatan, Kementerian Kesehatan RI; 2010. 8. Bell ML, Ebisu K, Belanger K. Ambient air pollution and low birth weight in Connecticut and Massachusetts. Environmental Health Perspective. 2007; 115: 1118-24. 9. Bobak M. Outdoor air pollution, low birth weight, and prematurity. Environmental Health Perspective. 2000; 108: 173-6. 10. Gouveia N, Bremner SA, Novaes HM. Association between ambient air pollution and birth weight in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004; 58: 11-7. 11. Ha EH, Hong YC, Lee BE, Woo BH, Schwartz J, Christiani DC. Is air pollution a risk factor for low birth weight in Seoul? Epidemiology. 2001; 12: 643-8. 12. Lee BE, Ha EH, Park HS, Kim YJ, Hong YC, Kim H. Exposure to air pollution during different gestational phases contributes to risks of low birth weight. Hum Reproduction. 2003; 18: 638-43. 13. Lin CM, Li CY, Mao IF. Increased risks of term low-birth-weight infants in a petrochemical industrial city with high air pollution levels. Archives of Environmental Health. 2004; 59: 663-8. 14. Liu S, Krewski D, Shi Y, Chen Y, Burnett RT. Association between gaseous ambient air pollutants and adverse pregnancy outcomes in Vancouver, Canada. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2003; 111: 1773-8. 15. Madsen C, Gehring U, Walker SE, Brunekreef B, Stigum H, Naess O. Ambient air pollution exposure, residential mobility and term birth weight in Oslo, Norway. Environmental Research. 2010; 110: 363-71. 16. Maroziene L, Grazuleviciene R. Maternal exposure to low-level air pollution and pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study. Environmental Health. 2002; 1: 6. 17. Morello-Frosch R, Jesdale BM, Sadd JL, Pastor M. Ambient air pollution exposure and full-term birth weight in California. Environmental Health.2010; 9: 44. 18. Salam MT, Millstein J, Li YF, Lurmann FW, Margolis HG, Gilliland FD. Birth outcomes and prenatal exposure to ozone, carbon monoxide, and particulate matter: results from the Children’s Health Study. Environmental Health Perspective. 2005; 113: 1638-44. 19. Mannes T, Jalaludin B, Morgan G, Lincoln D, Sheppeard V, Corbett S. Impact of ambient air pollution on birth weight in Sydney, Australia. Occup Environ Med. 2005; 62: 524-30. 20. Ballester F, Estarlich M, Iniguez C, Llop S, Ramon R, Esplugues A. air pollution exposure during pregnancy and reduced birth size: a prospective birth cohort study in Valencia, Spain. Environmental Health. 2010; 9: 6. 21. Mohorovic L. First two months of pregnancy - critical time for preterm delivery and low birthweight caused by adverse effects of coal combustion toxics. Early Human Development. 2004; 80:115-23. 22. Chen L, Yokel RA, Hennig B, Toborek M. Manufactured aluminum oxide nanoparticles decrease expression of tight junction proteins in brain vasculature. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 2008; 3: 286-95.

Recommended Citation

Oktora B , Susanna D .

Pajanan NO2 Bulan Pertama dan Kedua Kehamilan terhadap Bayi dengan Berat Badan Lahir Rendah.

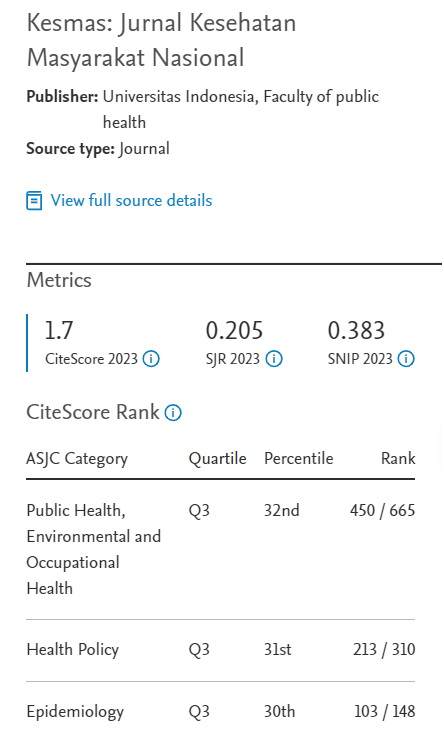

Kesmas.

2014;

8(6):

284-288

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v0i0.382

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol8/iss6/8