Abstract

Infeksi luka operasi (ILO) adalah bagian dari infeksi nosokomial dan merupakan masalah dalam pelayanan kesehatan, terjadi pada 2 - 5% dari 27 juta pasien yang dioperasi setiap tahun dan 25% dari jumlah infeksi terjadi di fasilitas pelayanan. Penelitian bertujuan mengetahui hubungan usia, status gizi, jenis operasi, lama rawat prabedah, kadar Hb, transfusi darah, waktu pemberian antibiotik profilaksis, jenis anestesi, lama pembedahan serta lama rawat pascabedah dengan kejadian ILO pada pasien pascabedah sesar di RSUP Dr. Sardjito Yogyakarta. Rancangan desain penelitian studi observasional prospektif dilakukan dengan sampel 154 orang. Data diperoleh melalui observasi menggunakan daftar tilik sejak pasien masuk rumah sakit sampai 30 hari pascabedah. Analisis data meliputi analisis univariat, analisis bivariat dengan menggunakan uji kai kuadrat serta analisis multivariat dengan uji regresi logistik berganda. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan ada hubungan antara waktu pemberian antibiotik profilaksis (OR = 1,16; 95% CI = 1,09 - 1,37), lama rawat prabedah (OR = 1,12; 95% CI = 1,02 - 1,24) dan lama rawat pascabedah (OR = 1,21; 95% CI = 1,04 - 1,39) dengan kejadian ILO. Faktor lainnya tidak mempunyai hubungan yang signifikan terhadap kejadian ILO. Hasil uji regresi logistik ganda menemukan lama rawat pascabedah merupakan faktor yang paling dominan terhadap kejadian ILO. Identifikasi faktor risiko ILO dapat bermanfaat untuk merencanakan upaya meminimalkan kejadian ILO pada pasien pascabedah sesar. Surgical site infection (SSI) is part of health care associated infection and remains a problem in hospital care. SSI occurs in 2 to 5% of the 27 million patients having surgery each year and 25% of infections occur in care facilities. This study aimed to relation various such as age, nutritional status, type of surgery, pre-operative length of stay, hemoglobin level, bloodtransfusions, timing of antibiotics prophylaxis, type of anesthesia, duration of operation and post-operative length of stay on the incidence of SSI post caesarean section at Dr. Sardjito Hospital Yogyakarta. Prospective observation study was conducted in 154 sample. Data were obtained through observations using checklist since hospital admission up to 30 days post surgery. Data analysis included univariate, chi-square test and multiple logistic regression. The result showed that time of prophylactic antibiotics (OR = 1.16; 95% CI = 1.09 - 1.37), pre-operative length of stay (OR = 1.12; 95% CI = 1.02 - 1.24) and post-operative length of stay (OR = 1.21; 95% CI = 1.04 - 1.39) were risk factors for SSI. Other factors did not show significant associations with incidence of the SSI. The findings from multiple logistic regression showed post-operative length of stay in hospital as the most dominant factor for incidence of SSI. Identifying SSI risk factors can be used to plan efforts to minimize the occurrence of SSI in post-caesarean section patients.

References

1. World Health Organization. World alliance for patient safety. Forward programme 2005 [manuscript on internet]. Geneve, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004 [cited 2012 Aug 5]. Available from: www.who.int/patientsafety 2. Sachin P, Mitesh H, Sangeeta P, Sameeta S, Dipa K. Surgical site infection: incidence and risk factors in a tertiary care hospital, Western India. National Journal of Community Medicine. 2012; 3 (2): 193-6. 3. Amenu D, Belachew T, Araya F. Surgical site infection and risk factors among obstetric cases of Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Southwest Ethopia. Ethiopia Journal Health Sciences. 2011; 21 (2): 91- 100 4. Grujovic ZR, Ilic MD. Surgical site infection in orthopedic patient; prospective cohort study in a University hospital in Serbia. Medicinski Glasnik. 2013; 10 (1): 148-52 5. Razavi SM, Ibrahimpoor M, Kashani AS, Jafarian A. Abdominal surgical site infections: incidence and risk factors at an Iranian Teaching Hospital. BMC Surgery. 2005; 5:1-5. 6. Jenks PJ, Laurent M, McQuarry S, Watkins R. Clinical and economic burden of surgical site infection (SSI) and predicted financial consequences of elimination of SSI from an English hospital. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2014; 86: 24-33 7. Gong SP, Guo HX, Zhou HZ, Chen L, Yu YH. Morbidity and risk factors for surgical site infection following caesarean section in Guangdong Province China. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2012; 38 (3): 509-15. 8. Gibson L, Bellizan J, Lauer J, Betran AP, Merialdi M, Althabe F. The global numbers and cost of additionally needed and unnecessary caesarean section performed per year: veruse as a barrier to universal coverage. Geneve, Switzerland: World Health Report; 2010. 9. Nazneen R, Begum RS, Sultana K. Rising trend of caesarean section in a tertiary hospital over a decade. Journal of Bangladesh College of Phycisians and Surgeon. 2011; 29 (3): 126-32. 10. Henman K, Gordon CL, Gardiner T, Thorn J, Spain B, Davies J, et al. Surgical site infections following caesarean section at Royal Darwin Hospital, Northern Territory. Healthcare Infection. 2012; 17: 47-51. 11. Johnson A, Young D, Reilly J. Caesarean section surgical site infection surveillance. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2006; 64: 30-5. 12. Mitt P, Lang K, Peri A, Maimets M. Surgical site infection following cesarean section in an Estonian University Hospital: postdischarge surveillance and analysis of risk factors. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2005; 26 (5): 449-54. 13. Wilson J, Wloch C, Lamagni T, Harrington P, Charlett A, Sheridan E. Risk factors for surgical site infection following cesarean section in England: results from a multicentre cohort study. International Journal of Obstetric and Gynaecology. BJOG. 2012; 119: 1324-33. 14. Ezechi OC, Edet A, Akinlade H, Gab- CV, Herbertson E. Incidence and rick factors for cesaerean wound infection in Lagos, Nigeria. BMC Research Notes. 2009; 2: 186. 15. Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 1999; 20 (4): 247-78. 16. Ghuman M, Rohlandt D, Joshy G, Lawrenson R. Post-caesarean section surgical site infection: rate and risk factors. The New Zealand Medical Journal. 2011; 124 (1339); 32-6. 17. Olsen MA, Butler AM, Willers DM, Devkota P, Gross GA, Fraser VJ. Risk factors for surgical site infection after low transverse cesarean section. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2008; 29: 477-84. 18. Namiduru M, Karaoglan I, Cam R, Bosnak V. Preliminary data from a surveillance study on surgical site infections and assessment of risk factors in a University Hospital. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences. 2013; 43: 156-62. 19. Smaill F, Gyte G. Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for preventing infection after cesarean section (review). Cochrane Database Sys Rev [serial on internet]. 2010 Jan [cited 2012 Jan 5]; 1: CD007482. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4007637/. 20. Costantine MM, Rahman M, Ghulmiyah L, Byers BD, Longo M, Wen T, et al. Timing of perioperative antibiotics for cesarean delivery : a metaanalysis. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2008; 199 (301):1-6. 21. Brown J, Thompson M, Sinnya S, Jeffery A, Costa CD, Woods C, et al. Pre-incision antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the incidence of post-caesarean surgical site infection. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2013; 83: 68- 70. 22. Royal College of obstetricians and gynaecologists, National collaborating center for women’s and children health. Caesarean section NICE clinical guideline. London: Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2011. 23. World Health Organization. WHO guidelines for safe surgery 2009. Geneve, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009.

Recommended Citation

Rivai F , Koentjoro T , Utarini A ,

et al.

Determinan Infeksi Luka Operasi Pascabedah Sesar.

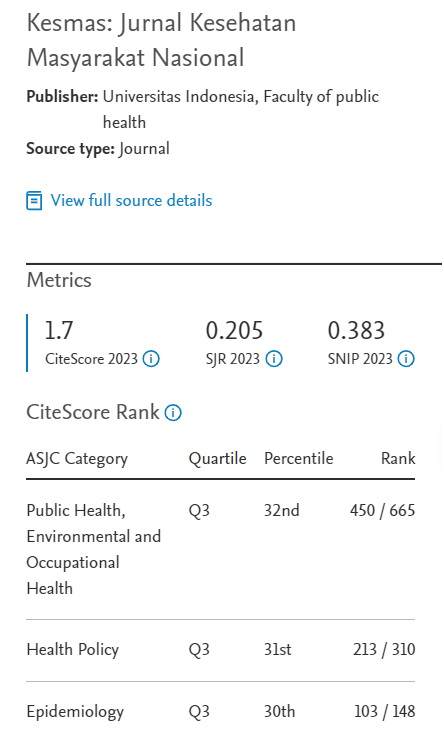

Kesmas.

2013;

8(5):

235-240

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v8i5.390

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol8/iss5/8