Abstract

Sindrom Metabolik (SM) merupakan faktor risiko penting penyakit kardiovaskuler yang merupakan penyebab utama kematian di Indonesia. Perbedaan gender pada SM berkontribusi terhadap perbedaan gender pada penyakit kardiovaskuler. Penelitian ini bertujuan mengetahui prevalensi dan risiko SM berdasarkan gender di perkotaan Indonesia menggunakan data Riset Kesehatan Dasar 2007 dan menggunakan rancangan penelitian potong lintang. Populasi penelitian terdiri dari 13.262 orang pria dan wanita yang tidak hamil berusia lebih dari 15 tahun yang bermukim di daerah perkotaan. Variabel penelitian meliputi variabel dependen sindrom metabolik. Variabel independen utama adalah gender dan variabel kovariat yang lain adalah level 1 (umur, status perkawinan, pendidikan, stres, merokok, dan aktivitas fisik), level 2 (pendapatan keluarga, konsumsi energi rumah tangga, konsumsi protein rumah tangga, konsumsi serat rumah tangga, anggota rumah tangga, dan balita dalam rumah tangga), dan level 3 (provinsi, status urban, dan Indeks Pembangunan Manusia (IPM)). Analisis dilakukan dengan multilevel regresi logistik. Hasil penelitian menyebutkan bahwa prevalensi SM adalah 17,5 %, prevalensi pada wanita (21,3%) lebih tinggi daripada pria (12,9%). Risiko sindrom metabolik berdasarkan gender bergantung pada status umur, pendidikan, dan perkawinan dari individu. Variasi kejadian SM berdasarkan pendapatan keluarga kecil (nilai MOR 1,21) dan variasi kejadian SM berdasarkan provinsi juga kecil (nilai MOR 1,18).

Metabolic Syndrome (MS) is an important factor for Cardiovascular Disease (CVD). One of the main causes of death in Indonesia is CVD. Gender differences in MS may contribute the gender differences in CVD. This study aimed to examine the prevalence and MS risk by gender in the urban population of Indonesia using Riskesdas 2007 data and cross-sectional design study. Population of study consisted of 13,262 men and non pregnant women over 15 years old lived in urban area. Variables included in this study are MS as the dependent variable and gender as the main independent variable. The covariate variables consisted of: level 1 variables (age, marital status, education, stress, smoking, and physical activity), level 2 (family outcome, household energy consumption, protein consumption, fiber consumption, members, and toddler under 5 years), level 3 (province, urban status, and human development index). Multilevel logistic regression used in data analysis. Result showed that prevalence of MS was 17,5%, on women (21.3%) was higher than men (12.9%). The risk of MS by gender was depent on age, educational level, and marital status of individual. The variation of MS occurrence among the family incomes was small (MOR 1.21), and the variation of MS occurrence among the provinces was also small (MOR 1.18).

References

1. Reddy KS, Yusuf S. Emerging epidemic of cardiovasculer in developing countries, NCBI; 2000 [cited 2012 Aug 2]. Available from: www.pubmed.gov

2. Rustika. Pengembangan Model penyuluhan faktor risiko penyakit jantung lansia melalui peran keluarga [cited 2012 Sept 12]. Available from: http://digilib.litbang.depkes.go.id

3. Kelishadi R, Derakhshan R, Sabet B, Sarrafzadegan N, Kahbazi M, Sadri GH, et al. The metabolic syndrome in hypertensive and normotensive subject: The Isfahan Healthy Heart programme. Annals Academy of Medicine Singapore. 2005; 34: 243_9.

4. Regitz-Zagrosek V, Lehmkuhl E, Weickert MO. Gender difference in the metabolic syndrome and their role for cardiovascular disease. Clinical Research in Cardiology. 2006; 95 (3): 136_47.

5. Csaszar A, Kekes E, Abel T. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome estimated by International Diabetes Federation criteria in a Hungarian population. Blood Press. 2006; 15: 101–6.

6. Steyn K, Kazenellenbogen JM, Lombard CJ, Bourne LT. Urbanization and the risk for chronic diseases of lifestyle in the black population of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa. Journal of Cardiovascular Risk 1997; 4: 135–42.

7. O’Donnell S, Condell S, Begley C, Fitzgerald T. Prehospital care pathway delay: gender and myocardial infarction. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006; 53(3): 268_76.

8. Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Every NR, Barron HV, Krumholz HM. Sexbased differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Participants. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999; 341(4): 217_25.

9. Central Statistics Office Ireland. Central Statistics Office Website. 2007 [cited 2012 Jul 15]. Available from: http://www.cso.ie/. Accessed May 8, 2009

10. Denton M, Walters V. Gender differences in structural and behavioural determinants of health analysis of the social production of health. Social Science and Medicine 1999; 48 (9): 1221_35.

11. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) 2002. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 106:3143–421. United States: NIH Publication; 2002.

12. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), Einhorn D, Reaven GM, Cobin RH, Ford E, Ganda OP, Handelsman Y, et al. American College of Endocrinology position statement on the insulin resistance syndrome.Endocrine Practice. 2003; 9: 237–52.

13. Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. 2002. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002; 287: 356_9.

14. Marquezine GF, Oliveira CM, Pereira AC, Krieger JE, Mill JG. 2008. Metabolic syndrome determinants in an urban population from Brazil: social class and gender-specific interaction. Int J Cardiol 129: 259–65

15. Park MJ, Yun KE, Lee GE, Cho HJ, Park HS. A cross-sectional study of socioeconomic status and the metabolic syndrome in Korean adults. Annual Epidemiology. 2007; 17(4): 320-6.

16. Santos Ana, Ebrahim C Shah, Barros Henrique. Gender, socio-economic status and metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and old adults. BMC Public Health. 2008; 8: 62.

17. Pannier B, Thomas F, Eschwege E, Bean K, Benetos A, Leomach Y, et al. Cardiovascular risk markers associated with the metabolic syndrome in a large French population: The “SYMFONIE” study. Diabetes and Metabolism. 2006; 32: 467–74.

18. Park HS, Yun YS, Park JY, Kim YS, Choi JM. Obesity, abdominal obesity, and clustering of cardiovascular risk factors in South Korea. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003; 12: 411–8.

19. Carr MC. The emergence of the metabolic syndrome with menopause. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003; 88: 2404–11.

20. Petri Nahas EA, Padoani NP, Nahas-Neto J, Orsatti FL, Tardivo AP, Dias R. Metabolic syndrome and its associated risk factors in Brazilian postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2009; 12 (5): 1_8.

21. Ramin H, Masoumeh S, Mohammad T, Katayoun R, Noushin M, Nizal S. Metabolic syndrome in menopausal transition: Isfahan Healthy Heart Program, a population based study. Diabetology and Metabolic Syndrome. 2010; 2: 59.

22. Dallongeville J, Marecaux N, Cottel D, Bingham A, Amouyel P. Association between nutrition knowledge and nutritional intake in middle-aged among polish men from Northern France. Public Health Nutrition. 2001; 4: 27–33.

23. Scannell-Desch E. 2003. Women’s adjustment to widowhood: theory, research, and interventions. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Service. 2003; 41: 28_36.

24. Hobfall SE, Cameron RP, Chapman HA, Gallagher RW. Social support and social coping in couples. In: Pierce GR, Sarason BR, Sarason IG, editors. handbook of social support and the family. New York: Plenum Publishing; 1996. p. 123_42.

25. Lipowicz A, Lopuszanska M. Marrital differences in blood pressure and the risk of hypertension among polish men. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2002; 20 (5): 421-7.

Recommended Citation

Bantas K , Yoseph HK , Moelyono B ,

et al.

Perbedaan Gender pada Kejadian Sindrom Metabolik pada Penduduk Perkotaan di Indonesia.

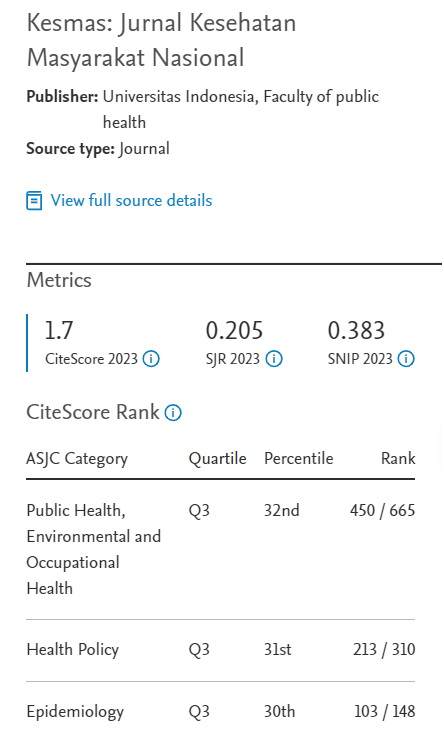

Kesmas.

2012;

7(5):

219-226

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v7i5.44

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol7/iss5/5