Abstract

Perhatian terhadap pencemaran udara ini menjadi semakin meningkat ketika banyak diketemukan dampaknya pada anak-anak, terutama kaitannya dengan insidens dan prevalens asma. Sumber utama pencemaran udara di Jakarta adalah dari kendaraan bermotor dan industri, dimana transportasi berkontribusi terhadap 71% NOX, 15% SO 2, dan 70% partikel debu kurang dari 10 mikronmeter (PM 10). Tujuan penelitian mengetahui jumlah partikel debu berdiameter ultrafine (partikel berukuran <0,1 mm) yang terhirup oleh anak sekolah dasar, pekerja pengguna kendaraan pribadi dan kendaraan umum. Studi ini menggunakan desain crosssectional dan dilakukan di Jakarta tahun 2005. Sebanyak 30 responden anak sekolah dasar, pekerja pengguna kendaraan pribadi dan kendaraan umum dipilih secara purposif sebagai subyek penelitian. Jumlah partikel ultrafine terhirup secara individu diukur selama 3 x 24 jam menggunakan Condensation Particle Counter (CPC) real time personal exposure measurement (jumlah ultrafine partikel per cm 3). Rerata konsentrasi partikel ultrafine terhirup pada anak sekolah dasar di rumah, di perjalanan, dan di sekolah adalah berurutan sebagai berikut: 29.254/cm 3, 147.897/cm 3 dan 61.033/cm 3. Pada pekerja pengguna kendaraan pribadi di rumah, di perjalanan, dan di kantor diperoleh rerata konsentrasi secara berurutan sebagai berikut: 29.213/cm 3, 310.179/cm 3 dan 42.496/cm 3. Sedangkan pada pekerja pengguna kendaraan umum adalah: 35.332/cm 3 di rumah, 453.547/cm 3 di perjalanan, dan 69.867/cm 3 di kantor. In Jakarta, the main pollution sources are vehicles and industry, with motorized traffic accounting for 71% of the oxides of nitrogen (NOX), 15% of sulphur-dioxide (SO2), and 70% of particulate matter (PM 10 ) of the total emission load. Both urban population size and the fraction of the population that owns a private vehicle are increasing. The study objective is to determine the numbers of ultrafine particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of 0.1 mm or less, or PM0.1 inhaled by elementary school children, commute workers with private car and commute workers with public transport. A cross-sectional study design is implemented in Jakarta 2005. Ten elementary school children, ten commuters with private car and ten commuters with public transports are purposively selected as subjects and measured personally for 3 x 24 hours using Condensation Particle Counter (CPC) real-time personal exposure measurement (measured in terms of the number of particles per cubic centimeter, or # cm-3). The average concentration of ultrafine particulate matter of elementary school children at home, on the road and at school is 29,254/cm3, 147,897/cm3 and 61,033/cm3 respectively. For those commuters with private car at home, on the road and at office is 29,213/cm3, 310,179/cm3 and 42,496/cm3 respectively. For those commuters with public transport, the concentration average of at home, on the road and at office is found higher: 35,332/cm3, 453,547/cm3, and 69,867/cm3, respectively.

References

1. Peters A, Wichmann HE, Tuch T, Heinrich J, Heyder J. Respiratory effects are associated with the number of ultrafine particles. American Journal Respiratory Critical Care Medicine. 1997; 155: 1376-83. 2. Ferin J, Oberdorster G, Penney DP. Pulmonary retention of ultrafine and fine particles in rats. American Journal of Respiratory Cell Molecular Biology. 1992; 6: 535-42. 3. MacNee W, Donaldson K. How can ultrafine particles be responsible for increased mortality? Monaldi Archive Chest Diseases. 2000; 55: 135-9. 4. Nemmar A, Vanbilloen H, Hoylaerts MF, Hoet PH, Verbruggen A, Nemery B. Passage of intratracheally instilled ultrafine particles from the lung into the systemic circulation in hamster. American Journal of Respiratory Critical Care Medicine. 2001; 164: 231-48. 5. Panther, BC, Hooper, MA, Tapper, NJ. Comparison of air particulate matter and associated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in some tropical and temperate urban environments. Atmospheric Environment. 1999; 33(24): 4087-99. 6. Utell MJ, Framtou MW. Acute health effects of ambient air pollution: the ultrafine particles hypothesis. Joutnal of Aerosol Medicine. 2000; 13: 355-9. 7. Tritugaswati A. Review of air pollution and its health impact in Indonesia. Environmental Research. 1993; 63(1): 95-100. 8. Ostro B. Outdoor air pollution: assessing the environmental burden of disease at national and local levels. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. http://www.who.int/quantifying_ehimpacts/publications/ebd5/en /index.html. 9. Pinandito M, Rosananto I, Hidayat I. Lidar network system for monitoring the atmospheric environment in Jakarta city. Optical Review. 1998; 5(4): 252-56. 10. Duki MI, Sudarmadi, Suzuki S, Kawada S, Tugaswati T Tri. A effect of air pollution on respiratory health in Indonesia and its economic cost. Archives of Environmental Health. 2003; 58(3): 135-43. 11. HEI International Scientific Oversight Committee. Health effects of outdoor air pollution in developing countries of Asia: A literature review. Special report 15. Boston, MA: Health Effects Institute; 2004. 12. Zou LY, Hooper MA. Size-resolved airborne particles and their morphology in central Jakarta. Atmospheric Environment. 1997; 31(8): 1167-72. 13. Cass GR, Hughes LA, Bhave P. The chemical composition of atmospheric ultrafine particles. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A. 2000; 358: 2581-92. 14. Wichmann HE and A Peters. Epidemiological evidence of the effects of ultrafine particle exposure. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series a-Mathematical Physical and Engineering Sciences. 2000; 358(1775): 2751-68. 15. Li N, Venkatesan MI, Miguel A. Indiction of heme oxygenase-1 expression in macrophages by diesel exhaust particle chemicals and quinones via antioxidant-responsive element. Journal of Immunology. 2000; 165(6): 3393-401.

Recommended Citation

Haryanto B .

Human Health Risk to Ultrafine Particles in Jakarta.

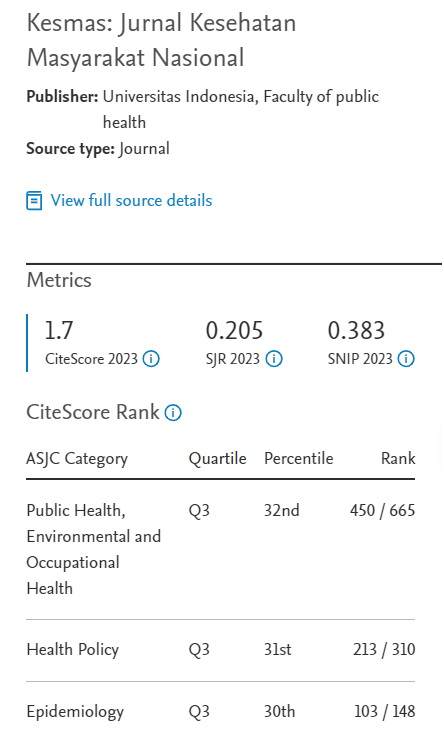

Kesmas.

2009;

4(2):

65-70

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v4i2.189

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol4/iss2/3