Abstract

The automotive industry is a significant source of volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions, particularly from solvent-based painting processes. This study evaluated VOC characteristics and distribution to assess associated health risks for workers and communities at varying distances from automotive painting facilities in Thailand, focusing on stacks and wastewater treatment plants that handle solvent-containing wastewater. The findings revealed aromatic compounds were predominant (66% of the total emissions), followed by oxygenated VOCs (26%). The stacks mainly emitted aromatics such as toluene and ethylbenzene, whereas the wastewater released oxygenated VOCs, particularly methyl isobutyl ketone and methyl ethyl ketone. The exposure concentrations in each area were primarily influenced by wind direction, with higher levels observed by downwind. The hazard index for areas was less than 1, indicating safe noncarcinogenic risk levels. The lifetime cancer risk showed that ethylbenzene posed a probable risk in all areas (maximum 8.15 × 10⁻⁶ μg/m³), whereas 1,2-dichloroethane exhibited a probable risk within 200 meters of the facility (maximum 4.13 × 10⁻⁵ μg/m³). This study supports the development of comprehensive emission standards covering health-related compounds and guides residential planning to avoid potential health impacts.

References

1. Kim JH, Moon N, Heo SJ, et al. Effects of environmental health literacy-based interventions on indoor air quality and urinary concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, volatile organic compounds, and cotinine: A randomized controlled trial. Atmos Poll Res. 2024; 15 (1): 101965. DOI: 10.1016/j.apr.2023.101965.

2. Rivera JL, Reyes-Carrillo T. A life cycle assessment framework for the evaluation of automobile paint shops. J Clean Prod. 2016; 115: 75-87. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.12.027.

3. Liu Z, Yan Y, Lv T, et al. Comprehensive understanding the emission characteristics and kinetics of VOCs from automotive waste paint sludge in a environmental test chamber. J Hazard Mater. 2022; 429: 128387. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128387.

4. Du Z, Li H, Nie L, et al. High-solution emission characters and health risks of volatile organic compounds for sprayers in automobile repair industries. Environ Sci Poll Res. 2024; 31: 22679-22693. DOI: 10.1007/s11356-024-32478-9.

5. United States Environmental Protection Agency. U.S. EPA Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS). Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency; 2001.

6. Li Y, Yan B. Human health risk assessment and distribution of VOCs in a chemical site, Weinan, China. Open Chem. 2022; 20 (1):192-203. DOI: 10.1515/chem-2022-0132.

7. Romanelli AM, Bianchi F, Curzio O, et al. F. Mortality and Morbidity in a Population Exposed to Emission from a Municipal Waste Incinerator. A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019; 16 (16): 2863. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph16162863.

8. Hsieh C-Y, Su C-C, Shao S-C, et al. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database: past and future. Clin Epidemiol. 2019; 11: 349-358. DOI: 10.2147/clep.s196293.

9. Saeaw N, Thepanondh S. Source apportionment analysis of airborne VOCs using positive matrix factorization in industrial and urban areas in Thailand. Atmos Poll Res. 2015; 6 (4): 644-650. DOI: 10.5094/APR.2015.073.

10. Keawboonchu J, Thepanondh S, Kultan V, et al. Unmasking the aromatic production Industry's VOCs: Unraveling environmental and health impacts. Atmos Environ X. 2024; 21: 100238. DOI: 10.1016/j.aeaoa.2024.100238.

11. Ou R, Chang C, Zeng Y, et al. Emission characteristics and ozone formation potentials of VOCs from ultra-low-emission waterborne automotive painting. Chemosphere. 2022; 305: 135469. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.135469.

12. Zhong Z, Sha QE, Zheng J, et al. Sector-based VOCs emission factors and source profiles for the surface coating industry in the Pearl River Delta region of China. Sci Total Environ. 2017; 583: 19-28. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.12.172.

13. Atamaleki A, Motesaddi Zarandi S, Massoudinejad M, et al. Emission of BTEX compounds from the frying process: Quantification, environmental effects, and probabilistic health risk assessment. Environ Res. 2022; 204: 112295. DOI: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.112295.

14. Shojaei A, Rostami R. BTEX concentration and health risk assessment in automobile workshops. Atmos Poll Res. 2024; 15 (12): 102306. DOI: 10.1016/j.apr.2024.10230.

15. Yu K, Xiong Y, Chen R, et al. Long-term exposure to low-level ambient BTEX and site-specific cancer risk: A national cohort study in the UK Biobank. Eco-Environ Health. 2025; 4 (2): 100146. DOI: 10.1016/j.eehl.2025.100146.

16. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Air Emission Measurement Center (EMC): Method 4 - Moisture Content. Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency; 2020.

17. Ciou Z-J, Ting Y-C, Hung Y-L, et al. Implications of photochemical losses of VOCs: An integrated approach for source apportionment, ozone formation potential and health risk assessment. Sci Total Environ. 2025; 958: 178009. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.178009.

18. Zhang F, Wang M, Wang M, et al. Revealing the dual impact of VOCs on recycled rubber workers: Health risk and odor perception. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2024; 283: 116824. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.116824.

19. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Clearinghouse for Inventories and Emissions Factors: WATER9, Version 3.0. Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency; 2006.

20. Ma Y, Fu S, Gao S, et al. Update on volatile organic compound (VOC) source profiles and ozone formation potential in synthetic resins industry in China. Environ Poll. 2021; 291: 118253. DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118253.

21. United States Environmental Protection Agency. User’s guide for the AMS/EPA regulatory model (AERMOD). Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency; 2019.

22. Yao X-Z, Ma R-C, Li H-J, et al. Assessment of the major odor contributors and health risks of volatile compounds in three disposal technologies for municipal solid waste. Waste Manag. 2019; 91: 128-138. DOI: 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.05.009.

23. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund (RAGS): Part F. Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency; 2025.

24. Omidi F, Dehghani F, Fallahzadeh RA, et al. Probabilistic risk assessment of occupational exposure to volatile organic compounds in the rendering plant of a poultry slaughterhouse. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019; 176: 132-136. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.03.079.

25. Li R, Yuan J, Li X, et al. Health risk assessment of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted from landfill working surface via dispersion simulation enhanced by probability analysis. Environ Poll. 2023; 316: 120535. DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120535.

26. Cheng Z, Sun Z, Zhu S, et al. The identification and health risk assessment of odor emissions from waste landfilling and composting. Sci Total Environ. 2019; 649: 1038-1044. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.230.

27. Huo S, Guan X, Li J, et al. Characteristics of VOCs in coating materials manufacturing and contributions to environmental implication based on on-site sampling in Shandong Province. J Environ Sci. 2025; 160: 497-507. DOI: 10.1016/j.jes.2025.05.014.

28. Wei G, Xiao Y, Wang J, et al. Environmental chamber analysis of objective volatile organic compounds emissions and subjective olfactory perception from main automotive interior components. Build Environ. 2024; 266: 112136. DOI: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2024.112136.

29. Xu Y, Bai L, Sun H, et al. Sector-based volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emission characteristics of metal surface coating industry and their emission reduction potential in Henan, China. J Environ Chem Eng. 2025; 13 (5): 118128. DOI: 10.1016/j.jece.2025.118128.

30. He CQ, Zou Y, Lv SJ, et al. The importance of photochemical loss to source analysis and ozone formation potential: Implications from in-situ observations of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in Guangzhou, China. Atmos Environ. 2024; 320: 120320. DOI: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.120320.

31. Li C, Li Q, Tong D, et al. Environmental impact and health risk assessment of volatile organic compound emissions during different seasons in Beijing. J Environ Sci (China). 2020; 93: 1-12. DOI: 10.1016/j.jes.2019.11.006.

32. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Proposed Guidelines for Neurotoxicity Risk Assesment Notice. Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency; 1995.

33. Chen J, Liu R, Gao Y, et al. Preferential purification of oxygenated volatile organic compounds than monoaromatics emitted from paint spray booth and risk attenuation by the integrated decontamination technique. J Clean Prod. 2017; 148: 268-275. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.040.

34. Chen W-H, Lin S-J, Lee F-C, et al. Comparing volatile organic compound emissions during equalization in wastewater treatment between the flux-chamber and mass-transfer methods. Process Saf Environ Protec. 2017; 109: 410-419. DOI: 10.1016/j.psep.2017.04.023.

35. Tyovenda AA, Ayua TJ, Sombo T. Modeling of gaseous pollutants (CO and NO2) emission from an industrial stack in Kano city, northwestern Nigeria. Atmos Environ. 2021; 253: 118356. DOI: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2021.118356.

36. Hu R, Liu G, Zhang H, et al. Levels, characteristics and health risk assessment of VOCs in different functional zones of Hefei. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2018; 160: 301-307. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.05.056.

37. Dehghani F, Omidi F, Heravizadeh O. Occupational health risk assessment of volatile organic compounds emitted from the coke production unit of a steel plant. Int J Occup Saf Ergonom. 2020; 26 (2): 227-232. DOI: 10.1080/10803548.2018.1443593.

38. Chelani AB. Fractal behaviour of benzene concentration near refinery, traffic junctions and residential locations in India. Atmos Poll Res. 2023; 14 (7): 101798. DOI: 10.1016/j.apr.2023.101798.

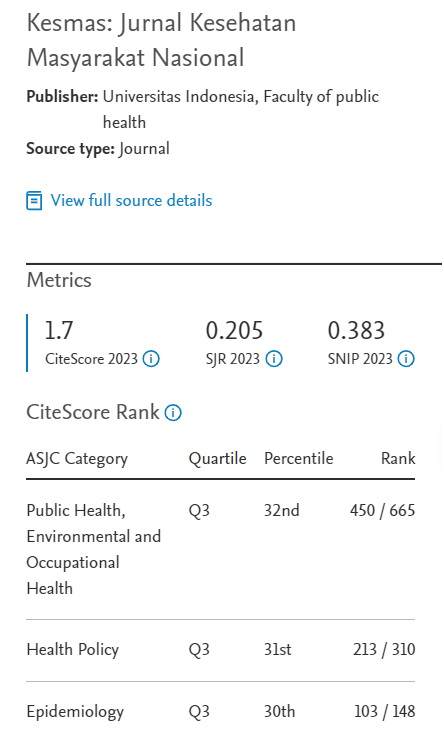

Recommended Citation

Kultan V , Thepanondh S , Keawboonchu J ,

et al.

Emission Characterization and Health Risk Assessment of Volatile Organic Compounds from Automotive Painting in Thailand.

Kesmas.

2025;

20(4):

314-324

DOI: 10.7454/kesmas.v20i4.2390

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol20/iss4/8

Included in

Environmental Health Commons, Environmental Public Health Commons, Occupational Health and Industrial Hygiene Commons