Abstract

A solution recommended by the World Health Organization to prevent and control noncommunicable diseases is the Sugar-Sweetened Beverage (SSB) tax. This study aimed to evaluate the Thai SSB tax efficiency affecting the change in post-tax individual-level consumption and find causal explanations for the people’s consumption behavior after the SSB tax was implemented. This study used a Productivity Model, and stratified random sampling was conducted by selecting 1,200 people. An in-depth interview was conducted to seek causal explanations for post-SSB tax consumption behavior with 15 key informants. The results revealed the SSB tax’s efficiency in terms of perception and understanding at 6.75% and in terms of awareness and compliance at 2.83%. Several reasons for the failure of such a policy included no price differences for products with and without sugar, lack of coverage in regulatory enforcement, addiction to sweet tastes, insufficient food literacy, and the dangers of artificial sweeteners. Therefore, a careful and comprehensive review and revision of the tax implementation is necessary. The integration of complementary policy instruments alongside the tax is also required.

References

1. Porter KMP, Rutkow L, McGinty EE. The importance of policy change for addressing public health problems. Public Health Reports. 2018; 133 (1 Suppl): 9S-14S. DOI: 10.1177/0033354918788880.

2. Busey E. Sugary drink taxes around the world. Chapel Hill; Carolina Digital Repository; 2020. DOI: 10.17615/2x4b-sr12.

3. World Health Organization. Workshop on implementing health taxes and other fiscal measures for prevention of noncommunicable diseases in the Pacific, Nadi, Fiji, 15-18 November 2022. Meeting report. Manila: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Western Pacific; 2022.

4. Phulkerd S, Thongcharoenchupong N, Chamratrithirong A, et al. Changes in population-level consumption of taxed and non-taxed sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) after implementation of SSB excise tax in Thailand: A prospective cohort study. Nutrients. 2020; 12 (11): 3294. DOI: 10.3390/nu12113294.

5. Bureau of Nutrition Ministry of Public Health. Fiscal measures on sugar sweetened beverages (SSBs): SSBs tax for good health and well-being of Thai people. Nonthaburi: Bureau of Nutrition Ministry of Public Health of Thailand; 2021.

6. Markchang K, Pongutta S. Monitoring prices of and sugar content in sugar-sweetened beverages from pre to post excise tax adjustment in Thailand. J Health Syst Res. 2019; 13 (2): 128–144.

7. Phonsuk P, Vongmongkol V, Ponguttha S, et al. Impacts of a sugar sweetened beverage tax on body mass index and obesity in Thailand: A modelling study. PloS one. 2021; 16 (4): e0250841. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250841.

8. Bisonyabut N. Answer the question directly: Lose weight and sweeten Thai people with taxes. Bangkok: Thailand Development Research Institute; 2016.

9. Cane and Sugar Administration Office. Sugar sales volume for domestic consumption, 4th quarter of 2023. Bangkok: Ministry of Industry of Thailand; 2024.

10. Division of Non-Communicable Diseases. Number and death rate from 5 non-communicable diseases (2017-2021). Nonthaburi: Ministry of Public Health of Thailand; 2023.

11. Pongsawatmanit R. Textural characteristics of Thai foods. In: Nishinari K, editor. Textural characteristics of world foods. Hobken, NJ: Wiley; 2020. p. 151-166. DOI: 10.1002/9781119430902.ch11.

12. Muangsri K, Tokaew W, Sridee S, et al. Health communication to reduce sugar consumption in Thailand. Func Food Health Dis. 2021; 11 (10): 484-498. DOI: 10.31989/ffhd.v11i10.833.

13. Nakamura R, Mirelman AJ, Cuadrado C, et al. Evaluating the 2014 sugar-sweetened beverage tax in Chile: An observational study in urban areas. PLoS medicine. 2018; 15 (7): e1002596. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002596.

14. Capacci S, Allais O, Bonnet C, et al. The impact of the French soda tax on prices, purchases and tastes: An ex post evaluation. PLoS ONE. 2019; 14 (10): e0223196. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223196.

15. Zhong Y, Auchincloss AH, Lee BK, et al. The short-term impacts of the Philadelphia beverage tax on beverage consumption. Am J Prev Med. 2018; 55 (1): 26-34. DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.02.017.

16. Allcott H, Lockwood BB, Taubinsky D. Should we tax sugar-sweetened beverages? An overview of theory and evidence. J Econ Perspect. 2019; 33 (3): 202-227. DOI: 10.1257/jep.33.3.202.

17. Gearhardt AN, Schulte EM. Is food addictive? A review of the science. Annu Rev Nutr. 2021; 41: 387-410. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-110420-111710.

18. Scaglioni S, De Cosmi V, Ciappolino V, et al. Factors influencing children’s eating behaviours. Nutrients. 2018; 10 (6): 706. DOI: 10.3390/nu10060706.

19. Thiboonboon K, Lourenco RDA, Church J, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in Thailand: Determinants and variation across socioeconomic status. Public Health. 2024; 237: 426-434. DOI: 10.1016/j.puhe.2024.10.037.

20. Vedung E. Public policy and program evaluation. 1st ed. New York: Routledge; 1997.

21. Bureau of Registration Administration. Announcement of population numbers for 2023-1999. Bangkok: Department of Provincial Administration of Thailand; 2022.

22. Yamashita A. Bangkok metropolitan area. In: Murayama Y, Kamusoko C, Yamashita A, Estoque R, editors. Urban Development in Asia and Africa: Geospatial analysis of metropolises. Springer; 2017. p. 151-169. DOI: 10.1007/978-981-10-3241-7_8.

23. Uakarn C, Chaokromthong K, Sintao N. Sample size estimation using Yamane and Cochran and Krejcie and Morgan and green formulas and Cohen statistical power analysis by G* Power and comparisons. APHEIT Int J Interdiscip Soc Sci Technol. 2021; 10 (2): 76–86.

24. Hedges LV. The statistics of replication. Methodology. 2019; 15 (Suppl 1): 3–14. DOI: 10.1027/1614-2241/a000173.

25. Bureau of Non-Communicable Diseases. 2016 Annual report. Nonthaburi: Ministry of Public Health of Thailand; 2016.

26. Thonrach T, Pisprasert V, Poldongnauk S. Healthy food. 1st ed. Khon Kaen: Health Promotion Unit, Social Medicine Work, Srinagarind Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Khonkaen University; 2015.

27. Taber KS. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ. 2018; 48: 1273–1296. DOI: 10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2.

28. Sauder DC, DeMars CE. An updated recommendation for multiple comparisons. Adv Method Pract Psychol Sci. 2019; 2 (1): 26-44. DOI: 10.1177/2515245918808784.

29. Acton RB, Vanderlee L, Adams J, et al. Tax awareness and perceived cost of sugar-sweetened beverages in four countries between 2017 and 2019: Findings from the international food policy study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2022; 19 (1): 38. DOI: 10.1186/s12966-022-01277-1.

30. Collin J, Hill S. Industrial epidemics and inequalities: The commercial sector as a structural driver of inequalities in non-communicable diseases. In: Smith KE, Hill S, Bambra C, editors. Health inequalities: Critical perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016.

31. Cherdkiattikul A. The reducing sweet consumption measures: Case study of the excise tax for beverages containing sugar or artificial sweeteners [Thesis]. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University; 2017.

32. Jindarattanaporn N, Rittirong J, Phulkerd S, et al. Are exposure to health information and media health literacy associated with fruit and vegetable consumption? BMC Public Health. 2023; 23: 1554. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-023-16474-1.

33. Eksangkul N, Nuangjamnong C. The factors affecting customer satisfaction and repurchase intention: A case study of bubble tea in Bangkok, Thailand. AU-HIU. 2022; 2 (2): 8-20.

34. National Food Institute. Thai food market report: Market of sweetened condensed milk, real cream, and non-dairy creamer in Thailand. Bangkok: Ministry of Industry of Thailand; 2017.

35. World Health Organization. WHO advises not to use non-sugar sweeteners for weight control in newly released guideline. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023.

36. Grand View Research. Sugar substitutes market size, share & trends analysis report by type (high-intensity sweeteners, high fructose syrup), by application (food, beverages), by region (North America, Asia Pacific), and segment forecasts, 2024 – 2030. San Francisco, United States; 2023.

37. Forberger S, Reisch L, Meshkovska B, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage tax implementation processes: Results of a scoping review. Health Res Policy Sys. 2022; 20 (1): 33. DOI: 10.1186/s12961-022-00832-3.

38. Parker C, Scott S, Geddes A. Snowball sampling. SAGE Research Methods Foundations; 2019.

Recommended Citation

Suriya S , Torut B .

Thai Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax: Does It Really Help?.

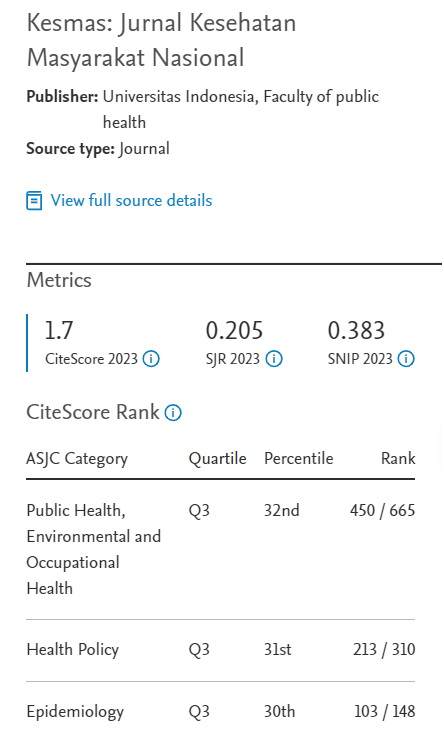

Kesmas.

2025;

20(1):

32-40

DOI: 10.7454/kesmas.v20i1.2081

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol20/iss1/5