Abstract

Indonesia’s neonatal mortality rate remains alarmingly high. This study addressed the determinants of neonatal outcomes in Indonesia, including the effects of a decentralized health system, socioeconomic disparities, and geographic variations. The analysis used 2018 national survey data across 34 provinces, 513 cities/districts, and 300,000 households, with a sample of 73,864 women aged 10-54 years who have given birth in the preceding five years. The multilevel regression was used to assess the impact of social determinants and systemic inequalities on neonatal health. Key findings revealed a neonatal mortality rate that, despite being preventable in many cases, remained high with significant disparities. The final model, incorporating individual and community-level factors, reduced unexplained variance by 28% (PCV), with community factors explaining 16% of the variability (ICC 0.1600). The community-level risk variability also decreased, as shown by a reduction in the Median Odds Ratio from 2.43 to 2.13. These results highlighted the importance of targeting individual and community factors to reduce the risk of babies being born at risk. There is a critical need for targeted health policies and local-specific interventions to bridge the equity gap and improve neonatal health outcomes.

References

1. Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional. Rancangan Akhir RPJPN 2025–2045. 2023.

2. Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional. Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 17 Tahun 2007 tentang Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Panjang Nasional Tahun 2005 – 2025. Jakarta: Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional; 2007.

3. Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional. Peraturan Presiden Nomor 18 Tahun 2020 tentang Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah Nasional 2020–2024. Jakarta: Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional; 2020.

4. Schumacher AE, Kyu HH, Aali A, et al. Global age-sex-specific mortality, life expectancy, and population estimates in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1950–2021, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: A comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024; 403 (10440): 1989–2056. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00476-8.

5. United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund. Indonesia: Child-related SDG indicators. New York: United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund; 2024.

6. Xin J, Luo Y, Xiang W, et al. Measurement of the burdens of neonatal disorders in 204 countries, 1990–2019: A global burden of disease-based study. Front Public Health. 2024; 11: 1282451. DOI: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1282451.

7. United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund. The State of children in Indonesia: Trends, opportunities, and challenges for realizing children’s rights. Jakarta: United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund Indonesia; 2020.

8. United Nations. SDGs Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. United Nations; 2024.

9. World Health Organization. SDG Target 3.2: End preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024.

10. Hug L, Liu Y, Nie W, et al. Levels and trends in child mortality United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME), Report 2023. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2024.

11. Oliveira R, Santinha G, Sá Marques T. The impacts of health decentralization on equity, efficiency, and effectiveness: A scoping review. Sustainability. 2024; 16 (1): 386. DOI: 10.3390/su16010386.

12. Sapkota S, Dhakal A, Rushton S, et al. The impact of decentralisation on health systems: A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Glob Health. 2023; 8 (12): e013317. DOI: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-013317.

13. Khemani S, Ahmad J, Shah S, et al. Decentralization and Service Delivery. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2005.

14. Badan Kependudukan dan Keluarga Berencana Nasional, Badan Pusat Statistik, Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia, The Demographic and Health Surveys Program. Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey 2017. Jakarta: Badan Kependudukan dan Keluarga Berencana Nasional, Badan Pusat Statistik, Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia, ICF; 2018.

15. Nigatu H, Solomon F, Soboksa N. The role of decentralization in promoting good governance in Ethiopia: The case of Wolaita and Dawuro Zones. Public Policy Adm Res. 2018; 8 (10): 42-57.

16. Joint Committee on Reducing Maternal and Neonatal Mortality in Indonesia, Development, Security, and Cooperation, Policy and Global Affairs, National Research Council, Indonesian Academy of Sciences. Reducing maternal and neonatal mortality in Indonesia: Saving lives, saving the future. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2013.

17. Dartanto T, Halimatussadiah A, Rezki JF, et al. Why do informal sector workers not pay the premium regularly? Evidence from the national health insurance system in Indonesia. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020; 18 (1): 81–96. DOI: 10.1007/s40258-019-00518-y.

18. Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. National Health Account Indonesia Tahun 2020. Jakarta: Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia; 2022.

19. McMaughan DJ, Oloruntoba O, Smith ML. Socioeconomic status and access to healthcare: Interrelated drivers for healthy aging. Front Public Health. 2020; 8: 231. DOI: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00231.

20. Shahid R, Shoker M, Chu LM, et al. Impact of low health literacy on patients’ health outcomes: A multicenter cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022; 22: 1148. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-022-08527-9.

21. Sarikhani Y, Najibi SM, Razavi Z. Key barriers to the provision and utilization of maternal health services in low-and lower-middle-income countries: A scoping review. BMC Women’s Health. 2024; 24: 325. DOI: 10.1186/s12905-024-03177-x.

22. Miller S, Abalos E, Chamillard M, et al. Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: A pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide. Lancet. 2016; 388 (10056): 2176–2192. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31472-6.

23. Marvin-Dowle K, Kilner K, Burley VJ, et al. Impact of adolescent age on maternal and neonatal outcomes in the Born in Bradford cohort. BMJ Open. 2018; 8 (3): e016258. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016258.

24. Neal S, Channon AA, Chintsanya J. The impact of young maternal age at birth on neonatal mortality: Evidence from 45 low- and middle-income countries. PLoS One. 2018; 13 (5): e0195731. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195731.

25. Xiong QF, Zhou H, Yang L, et al. Impact of maternal age on perinatal outcomes in twin pregnancies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. 2022; 26 (1): 99-109. DOI: 10.26355/eurrev_202201_27753.

26. Badan Pusat Satistik, United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund, Kementerian Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional/Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional, Center on Child Protection & WellBeing. Pencegahan perkawinan anak: Percepatan yang tidak bisa ditunda. Jakarta: Badan Pusat Satistik, United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund, Kementerian Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional/Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional, Center on Child Protection & WellBeing; 2020.

27. United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund, Center on Child Protection & WellBeing, Badan Pusat Satistik, Kementerian Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional/Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional. Child marriage factsheet 2020. Jakarta: United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund, Center on Child Protection & WellBeing, Badan Pusat Satistik, Kementerian Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional/Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional; 2020.

28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy complications at a glance. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2024.

29. Hajizadeh M, Nghiem S. Does unwanted pregnancy lead to adverse health and healthcare utilization for mother and child? Int J Public Health. 2020; 65 (4): 457–468. DOI: 10.1007/s00038-020-01358-7.

30. Li H, Bowen A, Bowen R, et al. Mood instability, depression, and anxiety in pregnancy and adverse neonatal outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021; 21 (1): 583. DOI: 10.1186/s12884-021-04021-y.

31. Dave DM, Yang M. Maternal and fetal health effects of working during pregnancy. Rev Econ Househ. 2022; 20 (1): 57–102. DOI: 10.1007/s11150- 020-09513-y.

32. McDermott-Murphy C. Do high-stress jobs put pregnancy at risk? The Harvard Gazette; 2024.

33. Abadiga M, Mosisa G, Tsegaye R, et al. Determinants of adverse birth outcomes among women delivered in public hospitals of Ethiopia, 2020. Arch Public Health. 2022; 80 (1): 12. DOI: 10.1186/s13690-021-00776-0.

34. Hollowell J, Oakley L, Kurinczuk JJ, et al. The effectiveness of antenatal care programmes to reduce infant mortality and preterm birth in socially disadvantaged and vulnerable women in high-income countries: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011; 11: 13. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2393-11-13.

35. Namazzi G, Hildenwall H, Ndeezi G, et al. Health facility readiness to care for high-risk newborn babies for early childhood development in eastern Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022; 22: 306. DOI: s12913-022-07693-0.

36. United States Agency for International Development. Strengthening the referral system for maternal and neonatal survival: Connecting facilities to improve emergency care. Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development; 2016.

37. Yap WA, Pambudi ES, Marzoeki P, et al. Revealing the missing link: Private sector supply-side readiness for primary maternal health services in Indonesia. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2017.

38. Narayanan I, Nsungwa-Sabiti J, Lusyati S, et al. Facility readiness in low- and middle-income countries to address care of high-risk/small and sick newborns. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2019; 5: 10. DOI: 10.1186/s40748-019-0105-9.

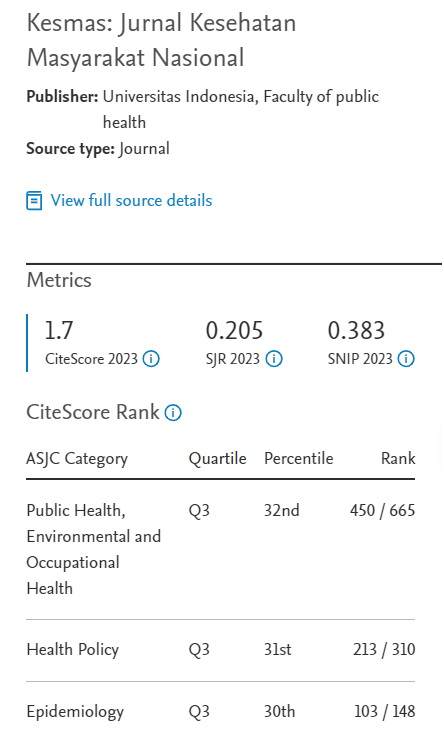

Recommended Citation

Soeharno R , Sjaaf AC .

Social Determinants of Neonatal Health Outcomes in Indonesia: A Multilevel Regression Analysis.

Kesmas.

2024;

19(4):

282-291

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v19i4.2034

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol19/iss4/8