Abstract

This study investigated the impact of economic growth and income distribution on health inequality using data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Employing a panel analysis, this study amalgamated 21 years of data (spanning from 2000 to 2020) from 37 OECD countries. The dependent variables (life expectancy and avoidable mortality) were scrutinized against independent variables (gross domestic product and poverty gap). Control variables encompassed body mass index, consumption patterns, smoking rates, health workers availability, number of beds in health facilities, national medical expenses, and unemployment rates. This study revealed significant associations between economic growth, poverty gap, and both life expectancy and avoidable mortality. This underscored the necessity of prioritizing not only income distribution but also overall economic growth to address health inequality effectively. This study established that an increase in the poverty gap corresponded to elevated life expectancy and reduced avoidable mortality rates, suggesting a mechanism distinct from a medical security system targeting lower-income individuals or an enhancement of societal welfare. Proposing policy measures to alleviate health inequality, this study advocates for policy interventions to mitigate the adverse impacts of income inequality within healthcare policies.

References

1. Dusenberry J. Income, saving and the theory of consumer behaviors. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1949.

2. Easterlin RA, O’Connor KJ. The Easterlin paradox. In: Zimmermann KF, editor. Handbook of labor, human resources and population economics. Cham: Springer; 2022. p. 1–25. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-57365-6_184-2.

3. Doyal L, Pennell I. The political economy of health. London: Pluto Press; 1979.

4. Navarro V. Class, struggle, the state and medicine. London: Martin Robertson; 1978.

5. Townsend P. Individual or social responsibility for premature death? Current controversies in the British debate about health. Int J Health Serv. 1990; 20 (3): 373-392. DOI: 10.2190/9Q6H-2KE7-X6FN-3DK8.

6. Marmot MG. Improvement of social environment to improve health. The Lancet. 1998; 351 (9095): 57–60. DOI: 10.1016/S0140- 6736(97)08084-7.

7. Townsend P, Davidson N, Whitehead M. Inequalities in health: The Black Report and the Health Divide. London: Penguin Books; 1992.

8. Acheson D. Independent inquiry into inequalities in health report. UK: The Stationery Office; 2001.

9. Macinko J, Shi L, Starfield B, et al. Income inequality and health: Critical review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2003; 60 (4): 407–452. DOI: 10.1177/1077558703257169.

10. Karlsson M, Nilsson T, Lyttkens C, et al. Income inequality and health: Importance of a cross-country perspective. Soc Sci Med. 2010; 70 (6): 875–885. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.056.

11. Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Lochner K, et al. Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. AJPH Am J Public Health. 1997; 87 (9): 1491–1498. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.87.9.1491.

12. Asthana S, Halliday DJ. What works in tackling health inequalities? Pathways, policies, and practice through the life course. Bristol: The Policy Press; 2006.

13. Marmot M, Wilkinson R. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999.

14. Wilkinson RG. The impact of inequality: How to make sick societies healthier. London: Routledge; 2020.

15. Berkman LF, Kawachi I. Social epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University; 2000.

16. Wilkinson RG, Pickett K. The spirit level: Why greater equality makes societies stronger. New York: Bloomsbury Press; 2009.

17. Prasad A, Borrell C, Mehdipanah R, et al. Tackling health inequalities using urban HEART in the sustainable development goals era. J Urban Health. 2018; 95: 610–612. DOI: 10.1007/s11524-017-0165-y

18. Hosseinpoor AR, Bergen N, Schlotheuber A, et al. Measuring health inequalities in the context of sustainable development goals. Bull World Health Organ. 2018; 96 (9): 654-659. DOI: 10.2471/BLT.18.210401.

19. Rodgers GB. Income and inequality as determinants of mortality: An international cross-section analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2002; 31 (3): 533– 538. DOI: 10.1093/ije/31.3.533.

20. Wilkinson RG. Income and mortality. In: Wilkinson RG, editor. Class and health research and longitudinal data. London: Tavistock; 1986.

21. Wilkinson RG. Income distribution and life expectancy. Br Med J. 1992; 304 (6820): 165–168. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.304.6820.165.

22. Le Grand J. Inequalities in health: Some international comparisons. Eur Econ Rev. 1987; 31 (1-2): 182–191. DOI: 10.1016/0014- 2921(87)90030-4.

23. Hill TD, Jorgenson A. Bring out your dead!: A study of income inequality and life expectancy in the United States, 2000–2010. Health Place. 2018; 49: 1–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.11.001.

24. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Data Explorer; 2000-2020.

25. Easterlin RA. Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In: David P, Melvin W, editors. Nations and households in economic growth. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press; 1974.

26. Otu A, Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, et al. One country, two crises: What COVID-19 reveals about health inequalities among BAME communities in the United Kingdom and the sustainability of its health system? Int J Equity Health. 2022; 19: 189. DOI: 10.1186/s12939-020-01307-z.

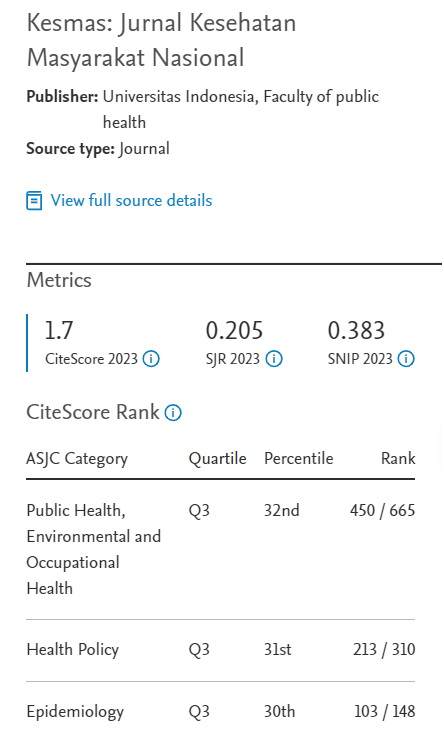

Recommended Citation

Han S .

Economic Growth, Poverty Gap, and Health Inequality: Implications Based on Panel Analysis of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Data.

Kesmas.

2024;

19(4):

272-281

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v19i4.2116

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol19/iss4/7