Abstract

Home births among ethnic minorities in developing countries pose significant risks to maternal and neonatal health. In Lao PDR, the government has taken steps to manage home births through training traditional birth attendants, improving transportation, and establishing referral systems. However, high home birth rates in regions like Bokeo remain concerning. This review emphasized the need for more skilled birth attendants and better access to emergency obstetric care in rural, ethnic minority areas. This review used 40 articles published between 2000 and 2023 and highlighted gaps in research regarding healthcare access, cultural practices, socioeconomic barriers, and the role of traditional birth attendants. Suggested strategies included scholarships for midwifery training, expanding telemedicine, enhancing emergency transport, and partnering with NGOs for culturally sensitive outreach. Although each strategy has limitations, collectively, they can improve maternal and newborn health outcomes and reduce home birth risks. Addressing cultural beliefs and preferences is essential to encourage healthcare use, and community engagement plays a key role in promoting safer birth practices while respecting traditions. A holistic approach combining skilled healthcare, cultural sensitivity, and accessible services is crucial to improving maternal and newborn care in ethnic minority communities in Lao PDR.

References

1. Quayle T. Factors associated with immediate postnatal care in Lao People's Democratic Republic: An analysis of the 2017 Lao People's Democratic Republic multiple indicator cluster survey [Dissertation]. Las Vegas: University of Nevada; 2022.

2. World Health Organization. Progress towards universal health coverage in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Monitoring financial protection 2007–2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023.

3. World Bank. Drivers of poverty in Lao PDR. Washington, DC: World Bank Group; 2020.

4. Noonan R. Education in the Lao People's Democratic Republic. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd; 2020.

5. Nanhthavong V, Epprecht M, Hett C, et al. Poverty trends in villages affected by land-based investments in rural Laos. Appl Geogr. 2020; 124: 102298. DOI: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2020.102298.

6. Kim SM. The effect of ethnic minorities policies of Southeast Asia on women's education and social advancement: A comparative study of Hmong Women in Laos and Thailand [Dissertation]. Seoul: Seoul National University; 2022.

7. Wungrath J, Chanwikrai Y, Khumai N, et al. Perception towards food choice among low-income factory worker parents of pre-school children in Northern Thailand: A qualitative study. Malays J Public Health Med. 2022; 22 (3): 98–106. DOI: 10.37268/mjphm/vol.22/no.3/art.1682.

8. Asian Development Bank. Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Country operations business plan (2019–2021). Manila: Asian Development Bank; 2019.

9. World Bank. Lao PDR economic monitor: Macroeconomic stability amidst uncertainty (English). Washington, DC: World Bank Group; 2019.

10. Kawaguchi Y, Sayed AM, Shafi A, et al. Factors affecting the choice of delivery place in a rural area in Laos: A qualitative analysis. PLoS One. 2021; 16 (8): e0255193. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255193.

11. Bouahom B, Kono Y. Challenges in responsible agricultural investment: Focusing on the development of the rubber industry in Laos. Kyoto Work Pap Area Stud. 2022; (136): 1–51.

12. Sato C, Phongluxa K, Toyama N, et al. Factors influencing the choice of facility-based delivery in the ethnic minority villages of Lao PDR: A qualitative case study. Trop Med Health. 2019; 47: 50. DOI: 10.1186/s41182-019-0177-2.

13. Kapheak K, Theerawasttanasiri N, Khumphoo P, et al. Perspectives of healthcare providers in maternal and child health services in Bokeo Province, Lao People’s Democratic Republic: A qualitative study. J Popul Soc Stud [JPSS]. 2024; 32: 329–345.

14. Uzir MUH, Al Halbusi H, Thurasamy R, et al. The effects of service quality, perceived value and trust in home delivery service personnel on customer satisfaction: Evidence from a developing country. J Retail Consum Serv. 2021; 63: 102721. DOI: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102721.

15. Alatinga KA, Affah J, Abiiro GA. Why do women attend antenatal care but give birth at home? A qualitative study in a rural Ghanaian district. PLoS One. 2021; 16 (12): e0261316. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261316.

16. Klasen S, Le TTN, Pieters J, et al. What drives female labour force participation? Comparable micro-level evidence from eight developing and emerging economies. J Dev Stud. 2021; 57 (3): 417–442. DOI: 10.1080/00220388.2020.1790533.

17. Scanlon A, Murphy M, Smolowitz J, et al. United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 3 target indicators: Examples of advanced practice nurses’ actions. J Nurse Pract. 2022; 18 (10): 1067–1070. DOI: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2022.03.005.

18. Feyisa JW, Merdassa E, Lema M, et al. Prevalence of homebirth preference and associated factors among pregnant women in Ethiopia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2023; 18 (11): e0291394. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0291394.

19. Hernández-Vásquez A, Chacón-Torrico H, Bendezu-Quispe G. Prevalence of home birth among 880,345 women in 67 low- and middle-income countries: A meta-analysis of demographic and health surveys. SSM Popul Health. 2021; 16: 100955. DOI: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100955.

20. Shah MA, Shah S, Shah AA. Cultural beliefs' influence on child health-seeking behavior in Laos and Pakistan: Exploring infant mortality rate. PLHR. 2023; 7 (4): 77–86. DOI: 10.47205/plhr.2023(7-IV)07.

21. Meemon N, Paek SC, Sherer PP, et al. Transnational mobility and utilization of health services in northern Thailand: Implications and challenges for border public health facilities. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021; 12. DOI: 10.1177/21501327211053740.

22. Kapheak K, Theerawasttanasiri N, Khumphoo P, et al. Exploring reasons and perspectives behind decisions to forego hospital births among remote rural populations in Bokeo Province, Lao PDR. NLS Nat Life Sci Commun. 2024; 23 (3): e2024040. DOI: 10.12982/NLSC.2024.040.

23. Sapphasuk W, Nawarat N. Cultural citizen’s conscience of migrant children in a Thailand–Lao PDR border school. Scholar Hum Sci. 2020; 12 (1): 262.

24. Wungrath J. Antenatal care services for migrant workers in Northern Thailand: Challenges, initiatives, and recommendations for improvement. J Child Sci. 2023; 13 (1): e118-e126. DOI: 10.1055/s-0043-1772844.

25. Appiah F, Owusu BA, Ackah JA, et al. Individual and community-level factors associated with home birth: A mixed effects regression analysis of 2017–2018 Benin demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021; 21: 547. DOI: 10.1186/s12884-021-04014-x.

26. Pimentel J, Ansari U, Omer K, et al. Factors associated with short birth interval in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20: 156. DOI: 10.1186/s12884-020-2852-z.

27. Win PP, Hlaing T, Win HH. Factors influencing maternal death in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam countries: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2024; 19 (5): e0293197. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0293197.

28. Horiuchi S, Nakdouangma B, Khongsavat T, et al. Potential factors associated with institutional childbirth among women in rural villages of Lao People’s Democratic Republic: A preliminary study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20: 89. DOI: 10.1186/s12884-020-2776-7.

29. World Health Organization. Managing programmes on reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

30. Ahmed S, Chase LE, Wagnild J, et al. Community health workers and health equity in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review and recommendations for policy and practice. Int J Equity Health. 2022; 21 (1): 49. DOI: 10.1186/s12939-021-01615-y.

31. Lee S, Adam AJ. Designing a logic model for mobile maternal health e-voucher programs in low- and middle-income countries: An interpretive review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 19 (1): 295. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph19010295.

32. Shiferaw BB, Modiba LM. Why do women not use skilled birth attendance service? An explorative qualitative study in north West Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20: 633. DOI: 10.1186/s12884-020-03312-0.

33. Ameyaw EK, Dickson KS. Skilled birth attendance in Sierra Leone, Niger, and Mali: Analysis of demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20: 164. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-020-8258-z.

34. Rahman M, Taniguchi H, Nsashiyi RS, et al. Trend and projection of skilled birth attendants and institutional delivery coverage for adolescents in 54 low- and middle-income countries, 2000–2030. BMC Med. 2022; 20: 46. DOI: 10.1186/s12916-022-02255-x.

35. Manyazewal T, Woldeamanuel Y, Blumberg HM, et al. The potential use of digital health technologies in the African context: A systematic review of evidence from Ethiopia. NPJ Digit Med. 2021; 4: 125. DOI: 10.1038/s41746-021-00487-4.

36. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations: Intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

37. Kapheak K, Theerawasttanasiri N, Khumphoo P, et al. Developing a social media-based communication system between rural healthcare providers and expert medical personnel in Bokeo Province, Laos PDR. JPSS J Popul Soc Stud. 2024; 32: 650–668. DOI: 10.25133/JPSSv322024.038.

38. Okonofua FE, Ntoimo LF, Adejumo OA, et al. Assessment of interventions in primary health care for improved maternal, newborn and child health in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. SAGE Open. 2022; 12 (4): 21582440221134222. DOI: 10.1177/21582440221134222.

39. Porru S, Misso FE, Pani FE, et al. Smart mobility and public transport: Opportunities and challenges in rural and urban areas. J Traffic Transp Eng (Engl Ed). 2020; 7 (1): 88–97. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtte.2019.10.002.

40. Sanadgol A, Doshmangir L, Majdzadeh R, et al. Engagement of non-governmental organisations in moving towards universal health coverage: A scoping review. Glob Health. 2021; 17: 129. DOI: 10.1186/s12992-021-00778-1.

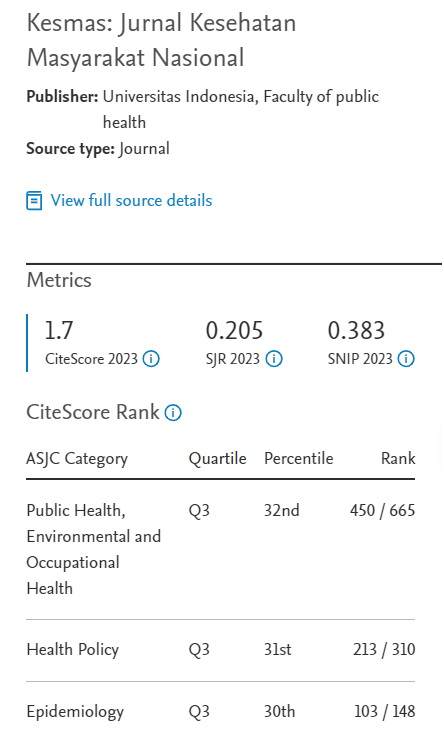

Recommended Citation

Wungrath J , Sriwongphan R , Kapheak K ,

et al.

Home Births Among Ethnic Minority Communities in Bokeo Province, Lao People's Democratic Republic.

Kesmas.

2024;

19(4):

264-271

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v19i4.1173

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol19/iss4/6