Abstract

An offshore platform is a workplace with complex facilities and limited space due to the complex installed equipment and components. Therefore, the offshoreas enclosed area platform is more likely to have a high risk of COVID-19 outbreak. Furthermore, a company must strictly follow health protocols to preventworkers from being exposed to COVID-19 in the offshore workplace. However, workers are often forced to onboard without proper health protocols becauseof operational needs and production targets. This paper aimed to explore the essence of the steps in preventing and controlling COVID-19 in the offshoreworkplace and the challenges. The analysis found that the company must take preventive measures against COVID-19 before workers are on board and inthe workplace and control it using the hierarchy of control: engineering control, administrative control, and personal protective equipment (PPE).

References

1.Aguiar-Quintana T, Nguyen H, Araujo-Cabrera Y, Sanabria-Díaz JM.Do job insecurity, anxiety and depression caused by the COVID-19pandemic influence hotel employees’ self-rated task performance? Themoderating role of employee resilience. International Journal ofHospitality Management. 2021; 94: 1-9. 2.Michaels D, Wagner GR. Occupational Safety and HealthAdministration (OSHA) and worker safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Jama. 2020; 324(14): 1389-90. 3.International Labour Organization. COVID-19 and the world of work,3rd ed. 2020; 1-23. 4.Liu X, Chang Y-C. An emergency responding mechanism for cruiseepidemic prevention - taking COVID-19 as an example. Marine Policy.2020; 119: 104093. 5.Chandrasekaran S. Dynamic analysis and design of offshore structures. New Delhi: Springer. 2015 p. 3. 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 employer information for offshore oil and gas; 2020. 7.George R, George A. Prevention of COVID-19 in the workplace.South African Medical Journal. 2020; 110(4): 1. 8.Cirrincione L, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: prevention and protectionmeasures to be adopted at the workplace. Sustainability. 2020; 12(9):3603. 9.Maersk G, Goodge A, McKechnie R. Medical aspects of fitness for offshore work: guidance for examining physicians. London: Oil & GasUK. 2008 p. 1-2. 10.Culica D, Rohrer J, Ward M, Hilsenrath P, Pomrehn P. Medical checkups: who does not get them?. American Journal of Public Health. 2002; 92(1): 88–91. 11.Palmer KT, Brown I, Hobson J. Fitness for work: the medical aspects,5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2019 p. 1-20. 12.Ejaz H, Alsrhani A, Zafar A, Javed H, Junaid K, Abdalla AE, et al.COVID-19 and comorbidities : deleterious impact on infected patients.Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2020; 13(12): 1833–39. 13.Jakhmola S, Indari O, Baral B, Kashyap D, Varshney N, Das A, et al.Comorbidity assessment is essential during COVID-19 treatment.Frontiers in Pshysiology. 2020; 11: 984. 14.Offshore Operators Committee. COVID-19 management strategies foroffshore energy operations; 2020. 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Testing overview; 2021. 16.Cevik M, Tate M, Lloyd O, Maraolo AE, Schafers J, Ho A. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV viral load dynamics, duration of viralshedding, and infectiousness: a systematic review and meta-analysis.The Lancet Microbe. 2020; 5247(20): 1–10. 17.Gostic K, Gomez ACR, Mummah RO, Kucharski AJ, Lloyd-Smith JO.Estimated effectiveness of symptom and risk screening to prevent thespread of COVID-19. Epidemiology and Global Health. 2020; 9:e55570. 18.Quilty BJ, Clifford S, Flasche S, Eggo RM. Effectiveness of airportscreening at detecting travellers infected with novel coronavirus(2019-nCoV). Eurosurveillance. 2020; 25(5): 2000080. 19.World Health Organization. Public health surveillance for COVID-19:interim guidance; 2020. 20.Rueda-Garrido JC, Vicente-Herrero MT, Del Campo MT, Reinoso-Barbero L, de la Hoz RE, Delclos GL, et al. Return to work guidelinesfor the COVID-19 pandemic. Occupational Medicine. 2020; 70(5):300-05. 21.Gkiotsalitis K, Cats O. Optimal frequency setting of metro services inthe age of COVID-19 distancing measures. Transpormetrica:Transport Science. 2021; 1–21. 22.Kampf G, Todt D, Pfaender S, Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidalagents. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2020; 104(3): 246–51. 23.Wu YC, Chen CS, Chan YJ. The outbreak of COVID-19: an overview.Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 2020; 83(3): 217–20. 24.Dehghani F, Omidi F, Yousefinejad S, Taheri E. The hierarchy of preventive measures to protect workers against the COVID-19 pandemic:a review. Work. 2020; 67(4): 771-7. 25.Ray I. Viewpoint – Handwashing and COVID-19: simple, rightthere…? World Development. 2020; 135: 105086. 26.Gould DJ, Moralejo D, Drey N, Chudleigh JH, Taljaard M.Interventions to improve hand hygiene compliance in patient care.Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017; (9). 27.Jefferson T, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, Ferroni E, Al-Ansary LA,Bawazeer GA, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce thespread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database of SystematicReviews. 2020; (11): 1-310. 28.Sun C, Zhai Z. The efficacy of social distance and ventilation effectiveness in preventing COVID-19 transmission. Sustainable Cities andSociety. 2020; 62: 102390. 29.Yang J, Sekhar SC, Cheong KWD, Raphael B. Performance evaluationof a novel personalized ventilation–personalized exhaust system forairborne infection control. Indoor Air. 2015; 25(2): 176–87.

Recommended Citation

Sunandar H , Ramdhan DH .

Preventing and Controlling COVID-19: A Practical-Based Review in Offshore Workplace.

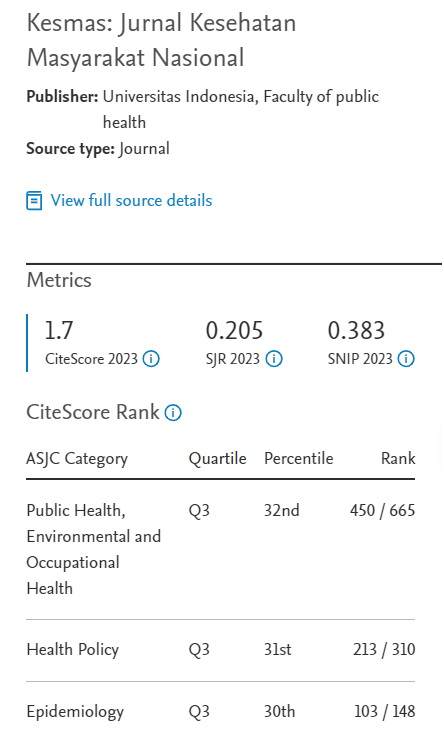

Kesmas.

2021;

16(5):

97-101

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v0i0.5226

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol16/iss5/17