Abstract

Running has become one of the most popular recreational sports worldwide. It is an easily accessible form of exercise as there are minimal equipment andsport structure requirements. Aerodynamic simulation experiments showed a risk of droplet exposure between runners when two people run in a straight lineat a close distance (slipstream). Thus, running activities require a safe physical distance of 10 meters to avoid droplet exposure, which can be a source oftransmission of COVID-19 infection. However, running outdoors during the COVID-19 pandemic is still often done in pairs and even in groups without wearinga mask. Open window theory stated that changes in the immune system occur immediately after strenuous physical activity. Many immune system componentsshowed adverse changes after prolonged strenuous activity lasting more than 90 minutes. These changes occurred in several parts of the body, such as theskin, upper respiratory tract, lungs, blood, and muscles. Most of these changes reflected physiological stress and immunosuppression. It is thought that an“open window” of the compromised immune system occurs in the 3–72-hour period after vigorous physical exercise, where viruses and bacteria can gain afoothold, increasing the risk of infection, particularly in the upper respiratory tract. Outdoor physical activity positively affects psychological, physiological, biochemical health parameters, and social relationships. However, this activity requires clear rules so that the obtained benefits can be more significant while simultaneously minimizing the risk of transmission of COVID-19 infection.

References

1. Hulteen RM, Smith JJ, Morgan PJ, Barnett LM, Hallal PC, Colyvas K, et al. Global participation in sport and leisure-time physical activities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med (Baltim). 2017;95:14–25. 2. Cloosterman KLA, van Middelkoop M, Krastman P, de Vos RJ. Running behavior and symptoms of respiratory tract infection during the COVID-19 pandemic: a large prospective Dutch cohort study. J Sci Med Sport. 2021;24(4):332–7. 3. Chomistek AK, Cook NR, Flint AJ, Rimm EB. Vigorous-intensity leisure-time physical activity and risk of major chronic disease in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(10):1898–905. 4. Swift DL, Lavie CJ, Johannsen NM, Arena R, Earnest CP, O’Keefe JH, et al. Physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and exercise training in primary and secondary coronary prevention. Circ J. 2013;77(2):281–92. 5. Ghorbani F, Heidarimoghadam R, Karami M, Fathi K, Minasian V, Bahram ME. The effect of six-week aerobic training program on cardiovascular fit-ness, body composition and mental health among female students. J Res Health Sci. 2014;14(4):264–7. 6. Janssen M, Walravens R, Thibaut E, Scheerder J, Brombacher A, Vos S. Understanding different types of recreational runners and how they use running-related technology. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7). 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19. CDC; 2021. 8. Greenhalgh T, Schmid MB, Czypionka T, Bassler D, Gruer L. Face masks for the public during the COVID-19 crisis. BMJ. 2020;369:1–4. 9. Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451–62. 10. Nieman DC, Wentz LM. The compelling link between physical activity and the body’s defense system. J Sport Heal Sci. 2019;8(3):201–17. 11. Blocken B, Malizia F, Druenen T Van, Marchal T. Towards aerodynamically equivalent COVID-19 1.5 m social distancing for walking and running. 2020;1–12. 12. Peake JM, Neubauer O, Walsh NP, Simpson RJ. Recovery of the immune system after exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2017;122(5):1077–87. 13. Simpson RJ, Katsanis E. The immunological case for staying active during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:6–7. 14. Walsh NP, Oliver SJ. Exercise, immune function and respiratory infection: an update on the influence of training and environmental stress. Immunol Cell Biol. 2016;94(2):132–9. 15. Dwyer MJ, Pasini M, De Dominicis S, Righi E. Physical activity: benefits and challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 2020;30:1291–4. 16. Wong AYY, Ling SKK, Louie LHT, Law GYK, So RCH, Lee DCW, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sports and exercise. Asia- Pacific J Sport Med Arthrosc Rehabil Technol. 2020;22:39–44. 17. Adiono AD, Bakhtiar Y, Supatmo Y, Muniroh M. Perbandingan efek olahraga indoor dan outdoor. J Kedokt Diponegoro. 2018;7(2):1088– 98. 18. Gladwell VF, Brown DK, Wood C, Sandercock GR, Barton JL. The great outdoors: how a green exercise environment can benefit all. Extrem Physiol Med. 2013;2(1):1–7. 19. Fannon C. A study of exercise environment and its effect on changes in mood: indoors vs outdoors; 2015. 20.Coon JT, Boddy K, Stein K, Whear R, Barton J, Depledge MH.Does participating in physical activity in outdoor naturalenvironments havea greater effect on physical and mental wellbeingthan physical activityindoors? A systematic review. Environ Sci& Technol. 2011;45(5):1761–72.21.Scudiero O, Lombardo B, Brancaccio M, Mennitti C, Cesaro A,Fimiani F, et al. Exercise, immune system, nutrition, respiratoryand cardiovascular diseases during COVID-19: a complexcombination. IntJ Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1–20.22.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang W, Ou C, He J, et al. Clinicalcharacteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl JMed. 2020;382(18):1708–20.23.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessonsfrom the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China:summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese center fordisease control and prevention. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc.2020;323(13):1239–42.24.Du Z, Xu X, Wu Y, Wang L, Cowling BJ, Meyers LA. Serialinterval of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases(COVID-19)-China, 2020. China CDC Weekly 2020. Res Lett.2020;26(6):2019–21.25.World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on physical activity,sedentary behaviour. World Health Organization. 2020 p. 104.26.World Health Organization. WHO global action plan on physicalactivity 2018-2030. World Health Organization. 2018 p. 101.27.Balducci S, Zanuso S, Nicolucci A, Fernando F, Cavallo S, CardelliP, et al. General physical activities defined by level of intensity.NutrMetab Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;20(8):608–17.28.Piotrowska K, Pabianek Ł. Physical activity – classification,characteristics and health benefits. Qual Sport. 2019;5(2):7.29.Woods JA, Hutchinson NT, Powers SK, Roberts WO, Gomez-CabreraMC, Radak Z, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and physicalactivity.Sport Med Heal Sci. 2020;2(2):55–64.30.Katewongsa P, Widyastari DA, Saonuam P, Haemathulin N,Wongsingha N. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on thephysical activity of the Thai population: evidence from Thailand’ssurveillance on physical activity 2020. J Sport Heal Sci. 2021;10(3):341–8.31.Li G, Fan Y, Lai Y, Han T, Li Z, Zhou P, et al. Coronavirusinfections and immune responses. J Med Virol. 2020;92(4):424–32.32.Barrett B, Hayney MS, Muller D, Rakel D, Brown R, Zgierska AE,et al. Meditation or exercise for preventing acute respiratoryinfection (MEPARI-2): a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One.2018;13(6):1–20.33.Rahmati-Ahmadabad S, Hosseini F. Exercise against SARS- CoV-2(COVID-19): does workout intensity matter? (A mini review of some indirect evidence related to obesity). Obes Med. 2020;19: 2018–20. 34.Arias FJ. Are runners more prone to become infected with COVID-19? An approach from the raindrop collisional model. J Sci SportExerc. 2021;3(2):167–70.

Recommended Citation

Makruf A , Ramdhan DH .

Outdoor Activity: Benefits and Risks to Recreational Runners during the COVID-19 Pandemic.

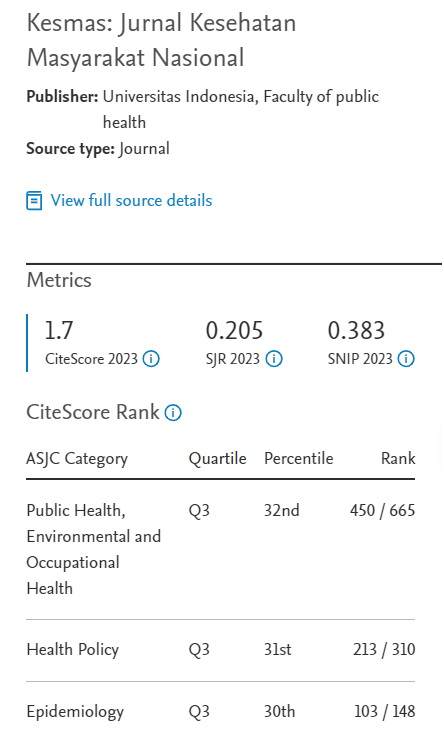

Kesmas.

2021;

16(5):

59-64

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v0i0.5223

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol16/iss5/12