Abstract

Five focus group discussions (FGDs) with 61 pregnant women were conducted in June and July 2019 at primary health care (PHC) services within five urban areas of Surabaya, Indonesia. In addition, five semi-structured interviews with five midwives were carried out to explore the experiences of pregnant women accessing Antenatal Care (ANC) and the factors shaping uptake of ANC services. Data were audio-recorded, transcribed, and translated into English, and analyzed using thematic analysis. Findings from focus group discussions suggested that fears of negative diagnosis before initial ANC appointment and personal beliefs and myths surrounding pregnancy may delay uptake of ANC. Further, the influence of husbands, family, and friends and long waiting times with overcrowding leading to limited seating shaped timely access and return visits. In addition, feeling comfortable with the quality of the service and receiving a friendly service from the practitioners assisted women in feeling comfortable to return. Finally, midwives acknowledged feeling afraid of being referred to a hospital if deemed a high-risk pregnancy-shaped return ANC visits. The findings highlighted several factors needing to be addressed to increase the promptness of first ANC visits and ensure return visits to achieve great ANC coverage.

References

1. Haftu A, Hagos H, Mehari M, G/her B. Pregnant women adherence level to antenatal care visit and its effect on perinatal outcome among mothers in Tigray public health institutions, 2017: cohort study. BMC Research Notes. 2018; 11 (1).

2. World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 2000 to 2017. World Health Organization; 2019.

3. Das A. Does antenatal care reduce maternal mortality?. Mediscope. 2017; 4 (1): 1-3.

4. Nababan HY, Hasan M, Marthias T, Dhital R, Rahman A, Anwar I. Trends and inequities in use of maternal health care services in Indonesia, 1986-2012. International Journal of Women's Health. 2018; 10: 11-24.

5. The United Nations Children Fund. Antenatal care - UNICEF DATA. UNICEF DATA; 2019.

6. World Health Organization. 2018 Health SDG profile: Indonesia. Searo.who.int; 2018.

7. Brooks M, Thabrany H, Fox M, Wirtz V, Feeley F, Sabin L. Health facility and skilled birth deliveries among poor women with Jamkesmas health insurance in Indonesia: a mixed-methods study. BMC Health Services Research. 2017; 17 (1).

8. Yap W, Pambudi E, Marxoeki P, Jwelwayne S, Tandon A. Maternal health report: revealing the missing link. Documents.worldbank.org; 2017.

9. Agus Y, Horiuchi S. Factors influencing the use of antenatal care in rural West Sumatra, Indonesia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2012;12 (1).

10. Efendi F, Chen C, Kurniati A, Berliana S. Determinants of utilization of antenatal care services among adolescent girls and young women in Indonesia. Women & Health. 2016; 57 (5): 614-29.

11. Fauk N, Cahaya I, Nerry M, Damayani A, Liana D. Exploring determinants influencing the utilization of antenatal care in Indonesia: a narrative systematic review. Journal of Healthcare Communications. 2017; 02 (04).

12. Schröders J, Wall S, Kusnanto H, Ng N. Millennium development goal four and child health inequities in Indonesia: a systematic review of the literature. PLOS ONE. 2015; 10 (5): e0123629.

13. Sujana T, Barnes M, Rowe J, Reed R. Decision making towards maternal health services in Central Java, Indonesia. Nurse Media Journal of Nursing. 2017; 6 (2): 68.

14. Rosales A, Sulistyo S, Miko O, Hairani L, Ilyana M, Thomas J, et al. Recognition of and care-seeking for maternal and newborn complications in Jayawijaya district, Papua Province, Indonesia: a qualitative study. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2017; 36 (S1).

15. Titaley C, Hunter C, Dibley M, Heywood P. Why do some women still prefer traditional birth attendants and home delivery?: a qualitative study on delivery care services in West Java Province, Indonesia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2010; 10 (1).

16. Ansariadi A, Manderson L. Antenatal care and women's birthing decisions in an Indonesian setting: does location matter?. Rural Remote Health. 2015; 15 (2): 2959.

17. Titaley C, Hunter C, Heywood P, Dibley M. Why don't some women attend antenatal and postnatal care services?: a qualitative study of community members' perspectives in Garut, Sukabumi and Ciamis districts of West Java Province, Indonesia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2010; 10 (1).

18. Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Weber MB. What influences saturation? Estimating sample sizes in focus group research. Qualitative Health Research. 2019; 29 (10): 1483-96.

19. Palinkas L, Horwitz S, Green C, Wisdom J, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2013; 42 (5): 533-44.

20. Dilshad R, Latif M. Focus group interview as a tool for qualitative research: an analysis. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences. 2013; 33 (1): 191-8.

21. DeJonckheere M, Vaughn L. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Family Medicine and Community Health. 2019; 7 (2): e000057.

22. Mills A, Durepos G, Wiebe E. Coding: selective coding. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research; 2010.

23. Heitmann K, Svendsen H, Sporsheim I, Holst L. Nausea in pregnancy: attitudes among pregnant women and general practitioners on treatment and pregnancy care. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care. 2016; 34 (1): 13-20.

24. Ebonwu J, Mumbauer A, Uys M, Wainberg M, Medina-Marino A. Determinants of late antenatal care presentation in rural and peri-urban communities in South Africa: a cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE. 2018; 13 (3): e0191903.

25. Ogbo F, Dhami M, Ude E, Senanayake P, Osuagwu U, Awosemo A, et al. Enablers and barriers to the utilization of antenatal care services in India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16 (17): 3152.

26. Yasuoka J, Nanishi K, Kikuchi K, Suzuki S, Ly P, Thavrin B, et al. Barriers for pregnant women living in rural, agricultural villages to accessing antenatal care in Cambodia: a community-based cross-sectional study combined with a geographic information system. PLOS ONE. 2018; 13 (3): e0194103.

27. Wulandari L, Klinken Whelan A. Beliefs, attitudes and behaviours of pregnant women in Bali. Midwifery. 2011; 27 (6): 867-71.

28. Haddrill R, Jones G, Mitchell C, Anumba D. Understanding delayed access to antenatal care: a qualitative interview study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014; 14 (1).

29. Teklesilasie W, Deressa W. Husbands’ involvement in antenatal care and its association with women’s utilization of skilled birth attendants in Sidama zone, Ethiopia: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2018; 18 (1).

30. Ekawati F, Claramita M, Hort K, Furler J, Licqurish S, Gunn J. Patients’ experience of using primary care services in the context of Indonesian universal health coverage reforms. Asia Pacific Family Medicine. 2017; 16 (1).

31. Paré G, Trudel M, Forget P. Adoption, use, and impact of e-booking in private medical practices: mixed-methods evaluation of a two-year showcase project in Canada. JMIR Medical Informatics. 2014; 2 (2): e24.

32. Feroz A, Perveen S, Aftab W. Role of mHealth applications for improving antenatal and postnatal care in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. 2017; 17 (1): 704.

33. Roberts J, Sealy D, Marshak H, Manda-Taylor L, Gleason P, Mataya R. The patient-provider relationship and antenatal care uptake at two referral hospitals in Malawi: a qualitative study. Malawi Medical Journal. 2015; 27 (4): 145-50.

34. Downe S, Finlayson K, Tunçalp Ö, Gülmezoglu A. Provision and uptake of routine antenatal services: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; 2019.

Recommended Citation

Jones L , Damayanti N , Wiseman N ,

et al.

Factors Shaping Uptake of Antenatal Care in Surabaya Municipality, Indonesia: A Qualitative Study.

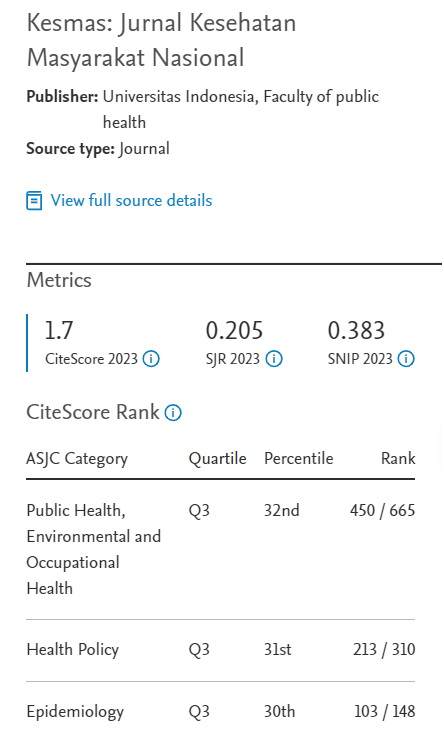

Kesmas.

2021;

16(3):

189-198

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v16i3.4849

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol16/iss3/8