Abstract

At the present time, an estimated of 673 million people defecate in the open space, not in private. Indonesia is a densely populated country with a lot of open defecation (OD) both in urban (37%) and rural areas (43%). Tanjung Karang Pusat Subdistrict is an area in Bandar Lampung City with the highest percentage of OD practice (45%). This study aimed to explore and explain the patterns and determinants of OD among urban people in the Tanjung Karang Pusat Subdistrict in- volving 377 respondents for quantitative analysis. Quantitative data were analyzed using the chi square and regression analysis. After controlling the economic status and education level variables, the data revealed that urban communities were still practicing OD (23.3%) with land ownership, latrine ownership, conative attitude, and occupation as influential factors. Statistical test results showed that the most influential factor in the behavior of OD in the community was latrine ownership (p-value <0.001, OR adj = 58.2). These findings suggested that stakeholders must take action on landowners who do not allow sanitation facilities to be built on their land.

References

- Steele R. Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene. New York: WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP). 2019; 140: 2000–17.

- Grojec A. Progress on sanitation and drinking water (2015 update and MDG assessment). Switzerland: UNICEF and World Health Organization; 2015.

- World Bank. Water supply and sanitation in Indonesia service delivery assessment turning finance into services; 2015.

- Cameron LA, Shah M. Scaling up sanitation: evidence from an RCT in Indonesia. Arc Discovery Projects. 2017; 10619: 34.

- Mara D. The elimination of open defecation and its adverse health effects: a moral imperative for governments and development professionals. Journal of Water, Sanitation & Hygiene for Development. 2017; 7 (1): 1–12.

- M Yalew BM. Prevalence and factors associated with stunting, underweight, and wasting: a community based cross sectional study among children age 6–59 months at Lalibela town, Northern Ethiopia. Journal of Nutritional Disorders & Therapy. 2014; 04 (2).

- Vyas S, Kov P, Smets S, Spears D. Disease externalities and net nutrition: evidence from changes in sanitation and child height in Cambodia, 2005–2010. Economics & Human Biology. 2016; 23: 235– 45.

- Clasen T, Boisson S, Routray P, Torondel B, Bell M, Cumming O, et al. Effectiveness of a rural sanitation programme on diarrhea, soiltransmitted helminth infection, and child malnutrition in Odisha, India: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Global Health. 2014; 2 (11): e645–53.

- Spears D. Exposure to open defecation can account for the Indian enigma of child height. Journal of Development Economics. 2018; 146: 1–17.

- World Health Organization. World health statistics: monitoring health for the SDGs. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Chaudhuri S, Roy M. Rural-urban spatial inequality in water and sanitation facilities in India: a cross-sectional study from household to national level. Applied Geography. 2017; 85: 27–38.

- Abubakar IR. Exploring the determinants of open defecation in Nigeria using demographic and health survey data. Science of the Total Environment. 2018; 637–8: 1455–65.

- Heijnen M, Routray P, Torondel B, Clasen T. Shared sanitation versus individual household latrines in urban slums: a cross-sectional study in Orissa, India. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2015; 93 (2): 263–8.

- Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Sanitasi LKA; 2019.

- Pelaksanaan P. Sanitasi total berbasis masyarakat dalam Program Kesehatan dan Gizi Berbasis Masyarakat (PKGBM); 2015.

- Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Laporan kemajuan ODF; 2019.

- Direktorat Jenderal Cipta Karya Kementerian Pekerjaan Umum dan Perumahan Rakyat Republik Indonesia. Petunjuk teknis SANIMAS reguler; 2017.

- O’Connell K. Water and sanitation program. What influences open defecation and latrine ownership in rural households?: findings from a global review; 2014. p.38.

- Vera Yulyani, Dina Dwi N, Dina Kurnia. Latrine use and associated factors among Rural Community in Indonesia. Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine. 2019; 19 (1): 143–51.

- Daley K, Castleden H, Jamieson R, Furgal C, Ell L. Water systems, sanitation, and public health risks in remote communities: Inuit resident perspectives from the Canadian Arctic. Social Science & Medicine. 2015; 135: 124–32.

- Kayoka C, Itimu-Phiri A, Biran A, Holm RH. Lasting results: a qualitative assessment of efforts to make community-led total sanitation more inclusive of the needs of people with disabilities in Rumphi District, Malawi. Disability and Health Journal. 2019; 12 (4): 10–3.

- Abramovsky L, Augsburg B, Flynn E, Oteiza F. Improving CLTS targeting: evidence from Nigeria. Economic & Social Research Council. 2016.

- Ryan TP. Sample size determination and power. United States: Wiley; 2013. p. 1–374

- Windsor RA. Evaluation of health promotion and disease prevention programs. Fifth edition. Madison Avenue: Oxford University Press; 2015.

- O’Reilly K. The influence of land use changes on open defecation in rural India. Applied Geography. 2018; 99: 133–9.

- Nunbogu AM, Harter M, Mosler HJ. Factors associated with levels of latrine completion and consequent latrine use in Northern Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16 (6): 920.

- Alemu F, Kumie A, Medhin G, Gasana J. The role of psychological factors in predicting latrine ownership and consistent latrine use in rural Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2018; 18: 229.

- Wankhade K. Urban sanitation in India: key shifts in the national policy frame. Environmentalist and Urban. 2015; 27 (2): 555–72.

- Shakya HB, Christakis NA, Fowler JH. Social network predictors of latrine ownership. Social Science & Medicine. 2015; 125: 129–38.

- Park MJ, Clements ACA, Gray DJ, Sadler R, Laksono B, Stewart DE. Quantifying accessibility and use of improved sanitation: towards a comprehensive indicator of the need for sanitation interventions. Scientific Reports. 2016; 6 (October 2015): 1–7.

- Mosler HJ, Mosch S, Harter M. Is community-led total sanitation connected to the rebuilding of latrines? quantitative evidence from Mozambique. PLOS ONE. 2018; 13 (5): e0197483

- Jain A, Fernald LCH, Smith KR, Subramanian SV. Sanitation in rural India: Exploring the associations between dwelling space and household latrine ownership. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16 (5): 734.

- Shiras T, Cumming O, Brown J, Muneme B, Nala R, Dreibelbis R. Shared latrines in Maputo, Mozambique: exploring emotional well-being and psychosocial stress. BMC International Health Human Rights. 2018; 18: 30.

- Patil SR, Arnold BF, Salvatore AL, Briceno B, Ganguly S, Colford JM, Gertler PJ. The effect of India’s total sanitation campaign on defecation behaviors and child health in rural Madhya Pradesh: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLOS Medicine. 2015; 11 (8): e1001709.

- Dickey MK, John R, Carabin H, Zhou XN. Program evaluation of a sanitation marketing campaign among the Bai in China: a strategy for cysticercosis reduction. Social Marketing Quarterly. 2015; 21 (1): 37– 50.

- Bardosh K. Achieving “total sanitation” in rural African geographies: Poverty, participation and pit latrines in Eastern Zambia. Geoforum. 2015; 66: 53–63.

- Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor 3 Tahun 2014 Tentang Sanitasi Total Berbasis Masyarakat; 2014.

- Desai R, Mcfarlane C, Graham S. The politics of open defecation: Informality, body, and infrastructure in Mumbai. Antipode. 2015; 47 (1): 98–120.

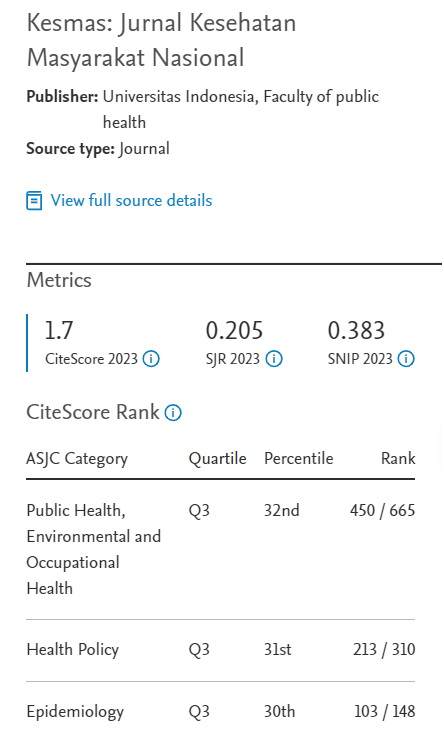

Recommended Citation

Yulyani V , Febriani CA , MS S ,

et al.

Patterns and Determinants of Open Defecation among Urban People.

Kesmas.

2021;

16(1):

45-50

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v16i1.3295

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol16/iss1/8

Included in

Biostatistics Commons, Environmental Public Health Commons, Epidemiology Commons, Health Policy Commons, Health Services Research Commons, Nutrition Commons, Occupational Health and Industrial Hygiene Commons, Public Health Education and Promotion Commons, Women's Health Commons