Abstract

Posyandu Remaja (Posmaja) is a community-based adolescent care service in Indonesia that comprises a group of adolescents working as volunteers and healthcare workers under the guidance and responsibility of the Public Health Centre and City Health Office. The study aims to provide a formative evaluation program of Posmaja using the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework. This research used a qualitative approach and took place in South Tangerang City, Indonesia. The data were collected from July until December 2018. Nineteen people participated in the study. The study used in-depth interviews and focus group discussions that adopted the RE-AIM framework for data collection. Content analysis was used to analyze the collected data. The majority of Posmaja’s participants were male adolescents aged around 15 years old. Common themes generated were “adolescent empowerment,” “increasing health knowledge,” and “monitoring health and nutrition” as a result of doing the pilot program. Volunteers and healthcare workers recognized the benefits of Posmaja and thus encouraged the adoption of the program. This awareness, followed by the city Health Office’s willingness to fund and adopt the program, was viewed as highly necessary for the program’s continuation.

References

1. Oey-Gardiner M, Gardiner P. Indonesia’s demographic dividend or window of opportunity?. Masyarakat Indonesia. 2013; 39 (2): 481– 504.

2. Hayes A, Setyonaluri D. Taking advantage of the demographic dividend in Indonesia: a brief introduction to theory and practice. Jakarta: UNFPA Indonesia; 2015.

3. World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia. Global youth tobacco survey (GYTS): Indonesia report 2014. New Delhi: WHO-SEARO. 2015; pp. 24.

4. Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Potret sehat Indonesia dari Riskesdas 2018; November 2, 2018.

5. World Health Organization. Global school-based student health survey: Indonesia 2015 fact sheet. 2015; 5: 1–6.

6. World Health Organization. Adolescent friendly health services: an agenda for change. World Health Organization; 2011.

7. Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Petunjuk teknis penyelenggaraan posyandu remaja. Jakarta: Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia; 2018.

8. Gaglio B, Shoup JA, Glasgow RE. The RE-AIM framework: a systematic review of use over time. American Journal of Public Health. 2013; 103 (6): e38–46.

9. King DK, Glasgow RE, Leeman-Castillo B. Reaiming RE-AIM: using the model to plan, implement, and evaluate the effects of environmental change approaches to enhancing population health. American Journal of Public Health. 2010; 100 (11): 2076–84.

10. Sweet SN, Ginis KAM, Estabrooks PA, Latimer-Cheung AE. Operationalizing the RE-AIM framework to evaluate the impact of multi-sector partnerships. Implementation Science. 2014; 9: 74.

11. Holtrop JS, Rabin BA, Glasgow RE. Qualitative approaches to use of the RE-AIM framework: rationale and methods. BMC Health Services Research. 2018; 18: 177.

12. Statistics of Tangerang Selatan Municipality. Tangerang Selatan municipality in figures; 2018.

13. Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2011; 11: 100 (1–9).

14. RE-AIM: Tools & Resources. Questions to ask about RE-AIM dimensions when evaluating health promotion programs and policies; 2016.

15. Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, Pölkki T, Utriainen K, Kyngäs H. Qualitative content analysis: a focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open. 2014; 4 (1).

16. Huye HF, Connell CL, Crook LSB, Yadrick K, Zoellner J. Using the RE-AIM framework in formative evaluation and program planning for a nutrition intervention in the lower Mississippi Delta. Journal of Nutrtion Education and Behavior. 2014; 46 (1): 34–42.

17. Church SP, Dunn M, Prokopy LS. Benefits to qualitative data quality with multiple coders: two case studies in multi-coder data analysis. Journal of Rural Social Sciences. 2019; 34(1): 2.

18. Faulkner SL, Trotter SP. Data saturation. In: Matthes J, Davis CS, Potter RF, editors. The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods; 2017.

19. Due P, Krølner R, Rasmussen M, Andersen A, Trab Damsgaard M, Graham H, et al. Pathways and mechanisms in adolescence contribute to adult health inequalities. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2011; 39 (6 suppl): 62–78.

20. Wong NT, Zimmerman MA, Parker EA. A typology of youth participation and empowerment for child and adolescent health promotion. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010; 46 (1–2): 100–14.

21. Koziarska-Rościszewska M, Wiśniewska K. The relationship between diet and other elements of lifestyle and the health status of adult high school students. Family Medicine & Primary Care Review. 2017; 19 (3): 230–4.

22. MacLellan J, Surey J, Abubakar I, Stagg HR, Mannell J. Using peer advocates to improve access to services among hard-to-reach populations with hepatitis C: a qualitative study of client and provider relationships. Harm Reduction Journal. 2017; 14 (1): 76.

23. Tobias CR, Rajabiun S, Franks J, Goldenkranz SB, Fine DN, LoscherHudson BS, et al. Peer knowledge and roles in supporting access to care and treatment. Journal of Community Health. 2010; 35 (6): 609– 17.

24. Sivagurunathan C, Umadevi R, Rama R, Gopalakrishnan S. Adolescent health: present status and its related programmes in India. Are we in the right direction?. Journal of Clinical & Diagnostic Research. 2015; 9 (3): LE01–6.

25. Nurmansyah MI, Al-Aufa B, Amran Y. Peran keluarga, masyarakat dan media sebagai sumber informasi kesehatan reproduksi pada mahasiswa. Jurnal Kesehatan Reproduksi. 2013; 3 (1): 16–23.

26. Abdi F, Simbar M. The peer education approach in adolescents- narrative review article. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2013; 42 (11): 1200-6.

27. Ceptureanu SI, Ceptureanu EG, Luchian CE, Luchian I. Community based programs sustainability. A multidimensional analysis of sustainability factors. Sustainability. 2018; 10 (3): 870.

Recommended Citation

Al Aufa B , Sulistiadi W , Nurmansyah MI ,

et al.

Using the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance Framework in the Evaluation of Community-Based Adolescent Care Pilot Program.

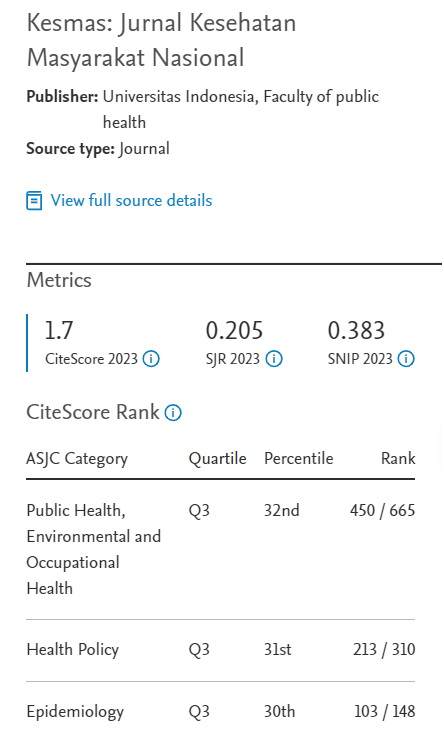

Kesmas.

2020;

15(4):

175-181

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v15i4.3812

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol15/iss4/4

Included in

Biostatistics Commons, Environmental Public Health Commons, Epidemiology Commons, Health Policy Commons, Health Services Research Commons, Nutrition Commons, Occupational Health and Industrial Hygiene Commons, Public Health Education and Promotion Commons, Women's Health Commons