Abstract

Walking is a public health recommendation to increase physical activity. Although walking for transport is associated with health benefits, it is frequently avoided when a mechanized alternative is available and when the weather or individuals’ available resources are unfavorable. The present quasi-experimental study used chosen walking speed to estimate the use of resources by pedestrians and investigated 730 pedestrians’ behavior when approaching a choice point between a short stair and a ramp at an exit from a university campus toward the local train station on six separate days. Results revealed that individuals who climbed the stairs walked faster than those who chose the ramp. In addition, females and those who were overweight walked slower than their comparator groups. Temperature was associated with walking behavior; as temperature increased, the walking speed of pedestrians decreased. Moreover, the purpose of walking is an important determinant of walking speed. Minimization of time to arrive at the train station as quickly as possible is a plausible alternative explanation for the effects of resource allocation on walking speed.

References

1. World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva, Switzerland; 2010.

2. Sallis JF. Needs and challenges related to multilevel interventions: physical activity examples. Health Education & Behavior. 2018; 45 (5): 661–7.

3. Saragiotto B, Pripas F, Almeida M, Yamato T. Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain in walkers: a cross-sectional study. Fisioterapia e Pesquisa. 2015; 22 (1): 29–33.

4. Yang Y, Diez-Roux A V. Adults’ daily walking for travel and leisure: interaction between attitude toward walking and the neighborhood environment. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2017; 31 (5): 435– 43.

5. Scholes S. Health survey for England 2016 physical activity in adults. NHS Digital; 2017.

6. Bemelmans RHH, Blommaert PP, Wassink AMJ, Coll B, Spiering W, van der Graaf Y, et al. The relationship between walking speed and changes in cardiovascular risk factors during a 12-day walking tour to Santiago de Compostela: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012; 2 (3): e000875.

7. C3 Collaborating for Health. The benefits of regular walking for health, well-being and the environment; 2012.

8. Celis-Morales CA, Lyall DM, Welsh P, Anderson J, Steell L, Guo Y, et al. Association between active commuting and incident cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mortality: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017; 357: j1456.

9. Hanson S, Jones A. Is there evidence that walking groups have health benefits? a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015; 49 (11): 710–5.

10. Mandini S, Conconi F, Mori E, Myers J, Grazzi G, Mazzoni G. Walking and hypertension: greater reductions in subjects with higher baseline systolic blood pressure following six months of guided walking. PeerJ. 2018; 2018 (8): 1–13.

11. Murtagh EM, Nichols L, Mohammed MA, Holder R, Nevill AM, Murphy MH. The effect of walking on risk factors for cardiovascular disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Prev Med (Baltim). 2015; 72: 34–43.

12. Park J-H, Miyashita M, Takahashi M, Kawanishi N, Hayashida H, Kim H-S, et al. Low-volume walking program improves cardiovascular-related health in older adults. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine. 2014; 13(3): 624–31.

13. Goodman A. Walking, cycling and driving to work in the English and Welsh 2011 census: trends, socio-economic patterning and relevance to travel behavior in general. PLoS One. 2013; 8 (8).

14. Department for Transport. 2016 national travel survey. National Travel Survey; 2017.

15. Bull FC, Biddle S, Buchner D, Ferguson R, Foster C, Fox K, et al. Physical activity guidelines in the UK: review and recommendations. British Heart Foundation National Centre for Physical Activity and Health. 2010; (May): 1–72.

16. US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical activity guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. Washington DC; 2018.

17. Merom D, Van Der Ploeg HP, Corpuz G, Bauman AE. Public health perspectives on household travel surveys: active travel between 1997 and 2007. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010; 39 (2): 113–21.

18. Spinney JEL, Millward H, Scott D. Walking for transport versus recreation: a comparison of participants, timing, and locations. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2012; 9 (2): 153–62.

19. Ussery EN, Carlson SA, Whitfield GP, Watson KB, Berrigan D, Fulton JE. Walking for transportation or leisure among U.S. women and men - national health interview survey, 2005–2015. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2017; 66 (25): 657–62.

20. Taylor KL, Fitzsimons C, Mutrie N. Objective and subjective assessments of normal walking pace, in comparison with that recommended for moderate intensity physical activity. International Journal of Exercise Science. 2010; 3 (3): 87–96.

21. Halsey LG, Watkins D a R, Duggan BM. The energy expenditure of stair climbing one step and two steps at a time: estimations from measures of heart rate. PLoS One. 2012 [cited 2014 Dec 3]; 7 (12): e51213.

22. Eves FF. Is there any profit in stair climbing? a headcount of studies testing for demographic differences in choice of stairs. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2014; 21 (1): 71–7.

23. Wagner AL, Keusch F, Yan T, Clarke PJ. The impact of weather on summer and winter exercise behaviors. Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2019; 8 (1): 39–45.

24. Harrison F, Goodman A, van Sluijs EMF, Andersen LB, Cardon G, Davey R, et al. Weather and children’s physical activity; how and why do relationships vary between countries?. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2017; 14 (1): 1–13.

25. Aspvik NP, Viken H, Ingebrigtsen JE, Zisko N, Mehus I, Wisløff U, et al. Do weather changes influence physical activity level among older adults? – the generation 100 study. PLoS One. 2018; 13 (7): 1–13.

26. Edwards N, Myer G, Kalkwarf H, Woo J, Khoury P, Hewett T, et al. Outdoor temperature, precipitation, and wind speed affect physical activity levels in children: a longitudinal cohort study.Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2015; 12 (8): 1074–81.

27. Clarke PJ, Yan T, Keusch F, Gallagher NA. The impact of weather on mobility and participation in older US adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2015; 105 (7): 1489–94.

28. Horiuchi M, Handa Y, Fukuoka Y. Impact of ambient temperature on energy cost and economical speed during level walking in healthy young males. Biology Open. 2018; 7 (7).

29. Klenk J, Büchele G, Rapp K, Franke S, Peter R. Walking on sunshine: effect of weather conditions on physical activity in older people. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2012; 66 (5): 474–6.

30. De Montigny L, Ling R, Zacharias J. The effects of weather on walking rates in nine cities. Environment and Behavior. 2012; 44 (6): 821– 40.

31. Hreljac A. Preferred and energetically optimal gait transition speeds in human locomotion. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 1993 Oct; 25 (10): 1158-62.

32. Teh KC, Aziz AR. Heart rate, oxygen uptake, and energy cost of ascending and descending the stairs. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2002; 34: 695–9.

33. Proffitt DR. Embodied perception and the economy of action. Perspect Psychological Science. 2006 Jun; 1 (2): 110–22.

34. Eves FF, Lewis AL, Griffin C. Modelling effects of stair width on rates of stair climbing in a train station. Prev Med (Baltim). 2008; 47 (3): 270–2.

35. Eves FF, Thorpe SKS, Lewis A, Taylor-Covill G a H. Does perceived steepness deter stair climbing when an alternative is available? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2014; 21 (3): 637–44.

36. Levine R V., Norenzayan A. The pace of life in 31 countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1999; 30 (2): 178–205.

37. McCardle W, Katch F, Katch V. Exercise physiology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, US: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2014. p. 1–1088.

Recommended Citation

Ekawati FF , Eves FF .

Effects of Climbing Choice, Demographic, and Climate on Walking Behavior.

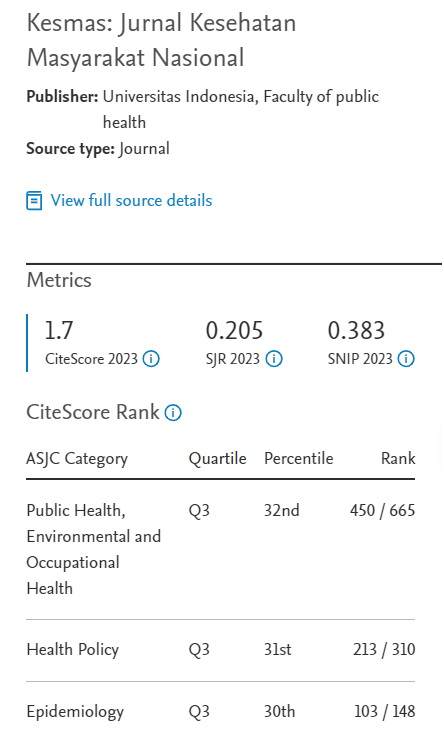

Kesmas.

2020;

15(2):

59-64

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v15i2.2909

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol15/iss2/3

Included in

Biostatistics Commons, Environmental Public Health Commons, Epidemiology Commons, Health Policy Commons, Health Services Research Commons, Nutrition Commons, Occupational Health and Industrial Hygiene Commons, Public Health Education and Promotion Commons, Women's Health Commons