Abstract

Keberlangsungan proses menyusui pada saat ibu kembali bekerja merupakan isu serius yang harus segera ditindaklanjuti agar program pemberian Air Susu Ibu (ASI) eksklusif selama enam bulan pertama kehidupan dapat tercapai. Selain memberikan banyak manfaat bagi bayi, ASI juga bermanfaat bagi ibu dan pengusaha. Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk mengetahui hubungan ibu bekerja terhadap pemberian ASI eksklusif. Desain penelitian yang digunakan adalah potong lintang dengan data sekunder Survei Demografi dan Kesehatan Indonesia (SDKI) tahun 2012 dengan sampel berjumlah 1.193 ibu berusia 15 – 49 tahun yang memiliki bayi berusia 0-5 bulan. Berdasarkan analisis multivariat, ibu bekerja dapat menurunkan peluang pemberian ASI eksklusif dimana ibu yang bekerja sepanjang waktu lebih berisiko 1,54 kali untuk tidak memberikan ASI eksklusif dibandingkan ibu yang tidak bekerja setelah dikontrol oleh usia melahirkan ibu, indeks kesejahteraan rumah tangga dan frekuensi pemeriksaan kehamilan (p = 0,038; CI 95% = 1,0 - 2,3). Ibu bekerja dua kali memiliki peluang untuk tidak dapat memberikan ASI eksklusif daripada ibu yang tidak bekerja setelah dikontrol oleh variabel perancu. Continuity of breastfeeding process when mothers return to work is a serious issue that immediately must be followed up, so that exclusive breastfeeding program within the first six months can be achieved. Beside providing many benefits for babies, breastfeeding is also beneficial for mothers and entrepreneurs. This study aimed to determine relation of working mothers to exclusive breastfeeding. This study used was cross- sectional design with secondary data of Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey 2012 with samples as many as 1,193 mothers aged 15 – 49 years who had 0 – 5-month-old babies. Based on multivariate analysis, working mothers could decrease opportunity of exclusive breastfeeding in which mother who worked all the time were 1.54 times more likely not to give exclusive breastfeeding than mothers who did not work after controlled by maternal age at childbirth, household wealth index, and antenatal care frequency (p = 0.038; 95% CI = 1.0 to 2.3). Fulltime working mothers are twofold more likely to not be able to give exclusive breasfedding than unemployed mothers after being controlled by counfounder variable.

References

1. Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional & The United Nations Children’s Fund. Periode emas pada 1000 hari pertama kehidupan. Buletin 1000 Hari Pertama Kehidupan. Jakarta: Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional & The United Nations Children’s Fund; 2013.

2. Khanal V, Aghikari M, Sauer K, Zhao Y. Factors associated with the introduction of prelacteal feeds in Nepal: finding from the Nepal demoghraphic and health survey 2011. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2013; 8: 1-9.

3. Roy MP, Mohan U, Singh SK, Singh VK, Srivastava AK. Determinants of prelacteal feeding in Rural Nothern India. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014; 5 (5): 658-63

4. Khanal V, Sauer K, Zhao Y. Exclusive breastfeeding practices in relation to social and health determinants: a comparison of the 2006 and 2011 Nepal demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13 (958):1-13.

5. Mekuria G, Edris M. Exclusive breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers in Debre Markos, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2015; 10 (1):1-7

6. Kamudoni P, Maleta K, Shi Z, Holboe-Ottesen G. Infant feeding practices in the first 6 months and associated factors in a rural and semiurban community in Mangochi District, Malawi. Journal Human Lactation. 2007; 23(4): 325-32.

7. Perez-Escamilla R, Segura-Millan S, Canahuati J, Allen H. Prelacteal feeds are negatively associated with breast-feeding outcomes in Honduras. Journal Nutrition. 1996; 126: 2765-73.

8. Wyatt S. Challenges of the working breastfeeding mother: workplace solutions. American Association of Occupational Health Nurses Journal. 2002; 50 (2): 61.

9. Mills SP. Workplace lactation programs: a critical element for breastfeeding mother’s success. American Association of Occupational Health Nurses Journal. 2009; 57 (6): 227-31.

10. Ekanem IA, Ekanem AP, Asuquo A, Eyo VO. Attitude of working mothers to exclusive breastfeeding in Calabar Municipality, cross river state, Nigeria. Journal of Food Research. 2012; 1(2): 71-5.

11. Abdullah GI. Determinan pemberian ASI Eksklusif pada ibu bekerja di Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia tahun 2012 [postgraduate thesis]. Depok: Fakultas Kesehatan Masyarakat Universitas Indonesia; 2012.

12. Dewi PM. Partisipasi tenaga kerja perempuan dalam meningkatkan pendapatan keluarga. Jurnal Ekonomi Kuantitatif Terapan. 2012; 5(2):119- 224.

13. Presiden Republik Indonesia. Peraturan Pemerintah Republik Indonesia Nomor 33 tahun 2012 tentang pemberian air susu ibu eksklusif. Jakarta: Kementerian Sekretariat Negara Republik Indonesia; 2012.

14. Presiden Republik Indonesia. Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 13 Tahun 2003 Tentang Ketenagakerjaan. Jakarta: Kementerian Sekretariat Negara Republik Indonesia; 2013.

15. Sartono A. Praktek menyusui ibu pekerja pabrik dan ibu tidak bekerja di Kecamatan Sukoharjo Kota Kabupaten Sukoharjo. Jurnal Gizi Universitas Muhammadiyah Semarang. 2013; 2(1): 9-17.

16. Badan Kependudukan dan Keluarga Berencana Nasional, Badan Pusat Statistik & Kementerian Kesehatan. Survei Demografi dan Kesehatan Indonesia (SDKI). Jakarta: Badan Kependudukan dan Keluarga Berencana Nasional, Badan Pusat Statistik & Kementerian Kesehatan; 2013.

17. Baale E. Determinants of early initiation, exclusiveness and duration of breastfeeding in Uganda. Journal Health Population Nutrition. 2014; 32 (2): 249-60.

18. Kurniawan B. Determinan keberhasilan pemberian air susu ibu eksklusif. Jurnal Kedokteran Brawijaya. 2013; 27(4): 236-40.

19. Soetjiningsih. ASI: petunjuk untuk tenaga kesehatan. Jakarta: EGC; 1997.

20. Titaley CR, Loh PC, Prasetyo S, Ariawan I, Shankar AH. Socio-economic factors and use of maternal health service are associated with delayed initiation and non-exclusive breastfeeding in Indonesia: secondary analysis of indonesia demographic and health surveys 2002/2003 and 2007. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2014; 23(1): 91-104.

21. Handayani H. Kendala pemanfaatan ruang asi dalam penerapan asi eksklusif di kementerian pemberdayaan perempuan dan perlindungan anak tahun 2011 [undergraduate thesis]. Depok: Fakultas Kesehatan Masyarakat Universitas Indonesia; 2012.

22. Rizkianti R, Prasodjo R, Novianti, Saptarini I. Analisis faktor keberhasilan praktik pemberian ASI eksklusif di tempat kerja pada buruh industri tekstil di Jakarta. Buletin Penelitian Kesehatan. 2014; 42 (4); 237- 48.

23. Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Peraturan menteri kesehatan Republik Indonesia nomor 15 tahun 2013 tentang tata cara penyediaan fasilitas khusus menyusui dan/atau memerah air susu ibu. Jakarta: Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia; 2013.

24. Menteri Negara Pemberdayaan Perempuan, Menteri Tenaga Kerja dan Transmigrasi, Menteri Kesehatan. Peraturan bersama Menteri Negara Pemberdayaan Perempuan, Menteri Tenaga Kerja, dan Transmigrasi, dan Meteri Kesehatan Nomor 48/MEN.PP/XII/2008, PER.27/MEN/XII/2008, dan 1177/MENKES/PB/XII/2008 Tahun 2008 tentang peningkatan pemberian air susu ibu selama waktu kerja di tempat kerja. Jakarta: Kementerian Pemberdayaan Perempuan, Kementerian Tenaga Kerja dan Transmigrasi, dan Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia; 2008.

25. Presiden Republik Indonesia. Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 36 Tahun 2009 tentang Kesehatan. Jakarta: Kementerian Sekretariat Negara; 2009.

Recommended Citation

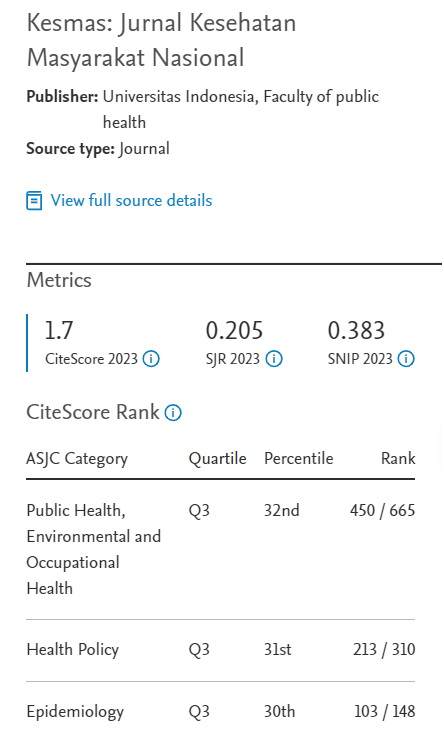

Sari Y .

Lack of Exclusive Breastfeeding among Working Mothers in Indonesia.

Kesmas.

2016;

11(2):

61-68

DOI: 10.21109/kesmas.v11i2.767

Available at:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/kesmas/vol11/iss2/3

Included in

Biostatistics Commons, Environmental Public Health Commons, Epidemiology Commons, Health Policy Commons, Health Services Research Commons, Nutrition Commons, Occupational Health and Industrial Hygiene Commons, Public Health Education and Promotion Commons, Women's Health Commons